Perspectives on world whisky: The rise & fall of Royal Welsh Whisky, 1889-1900

Image © St Fagan's National History Museum. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

SCOTLAND AND IRELAND are the traditional homes of whisky. What happened when whisky was first produced in Wales? Leon Kuebler investigates for WhiskyInvestDirect.

In the last decade, whisky has no longer remained the preserve of Scotland, Ireland and the United States. Japanese whisky, produced since the 1920s but rarely seen overseas until recent times, has become a phenomenal success, with many of the most expensive bottles at auction originating from Japan.

Recent years have seen the whisky map broaden further: distilleries can now be found in every continent on the planet, with ‘new world’ whiskies such as India’s Paul John and Taiwan’s Kavalan receiving a warm welcome among malt enthusiasts. At the same time, the ‘small is beautiful’ ethos of American craft distilling has reached Scotland, as nine micro-distilleries (to date) have opened alongside the traditional giants.

It is tempting to see the migration of whisky from its Celtic heartlands as a modern phenomenon, hitherto unknown. Yet the truth is that whisky has been produced in different times and places around the globe, with some ventures more successful than others. The case of The Welsh Whisky Company, the spiritual ancestor to the modern Welsh whisky distillery, Penderyn, gives a clear indication of the motives – and dangers – which world whisky has traditionally encountered.

Foundation

The Welsh Whisky Distillery Co. was founded in Frongoch, Bala in 1889. Frongoch was chosen for the distillery site due to the good transport links offered by the nearby railway station and ports. Water was taken from the Tai’r felin springs (after having received the approval of an ‘Analyst to the City of Edinburgh’ as to its suitability for distillation), while barley, peat and coal were all sourced locally. [i]

While Frongoch was the first Welsh distillery, it certainly was not a ‘craft’ distillery in any modern sense. The Welsh Distillery Company was founded with capital of £100,000 – the equivalent of around £10,000,000 in 2014 terms.[ii] When the distillery was completed in 1890, it was reported as having ‘a railway station on the ground… a commodious Malthouse, malt kilns, peat store, extensive offices and other accommodation required for working the unique concern’,[iii] while a dedicated excise officer was located on site.[iv] Full production capacity was anticipated to reach 150,000 gallons per annum;[v] this would have made Frongoch the 17th largest malt distillery in the United Kingdom.[vi] If we assume that these were proof gallons, the unit of trade of the day, this would equated to 390,000 LPA – small by today’s standards, but still 30% larger than the full capacity of its modern-day successor, Penderyn.

The Whisky

The first consignment of Welsh whisky, over 100 cases, was dispatched to customers in North Wales and border counties a year after production had commenced.[vii] In the following years, however, the company undertook a deliberate policy of restricting release until the whisky had matured. In the third annual meeting, the directors decided that ‘until the whisky had sufficient age to be placed before the public’, it was better ‘to limit the manufacture’ until the required quality for release was achieved.[viii] While the company recognised that success had been achieved in the first year from the ‘great novelty’, they noted that their whisky in late 1893 ‘was in bond still, and would, in all probability remain there for some time to come’, despite the problems this delay initially caused them.[ix] A year later, release was still scheduled for 1895, with another 100,000-150,000 gallon capacity warehouse built to house more maturing whisky in the meantime.[x]

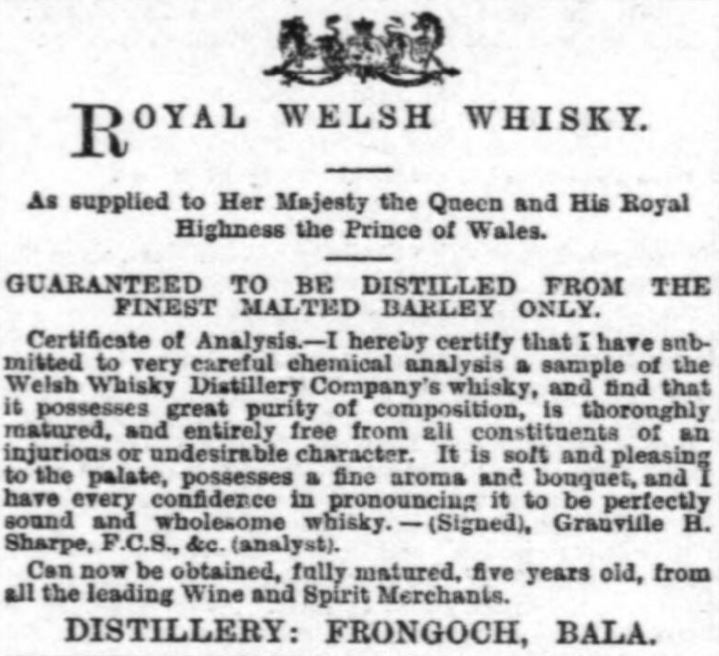

Source: The Welsh Whisky Co., Advertisement, Western Daily Press (20 Feb., 1896), p. 4.

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

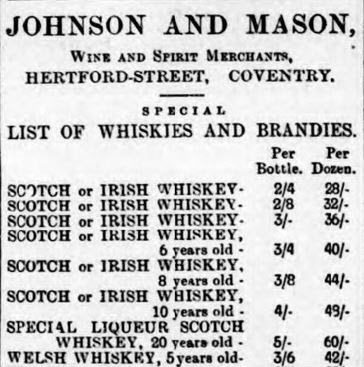

On 26 July, 1895, the Welsh Whisky Co. officially received a royal warrant from the Queen.[xi] Soon after, ‘Royal Welsh Whisky’ finally received a general release to the public in 1895. Little is known about the actual whisky itself. Adverts for Royal Welsh Whisky, such as the one above, state that the product was a five years old malt whisky. As Frongoch was in part chosen due to the ample peat available locally, it is highly likely that the whisky was peated, like most whiskies at the time. Welsh whisky was also comparatively expensive, priced at 3/6 compared to 3/4 for Scotch or Irish whiskies despite its younger age.

Source: Johnson & Mason, Advertisement, Coventry Herald (30 Mar., 1900), p. 5.

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

However, it is debateable whether Royal Welsh was a malt whisky in the Scottish sense. Every November from 1899 onwards, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record published a supplement entitled ‘Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom’. In each year which the Welsh Whisky Distillery was registered as active, its make was listed as ‘Pot Still’, a designation which was otherwise used exclusively for Irish distilleries.[xii] Other adverts from Charles R. Haig note that Royal Welsh could be purchased in both in bulk and bottle; a fact shared with their Irish whiskies, but not with Scotch.[xiii] As a whisky, Royal Welsh may therefore have been closer in style to its cousins across the Irish Sea, rather than whiskies made north of the border.

As is to be expected, no notes regarding its flavour have survived. The closest surviving ‘tasting note’, as such, comes from a reporter quoting a promotional document, which stated that:

‘Welsh whisky is the most wonderful whisky that ever drove the skeleton from the feast, or painted landscapes in the brain of man. It is the mingled souls of peat and barley, washed white with the waters of the Treweryn. In it you will find the sunshine and shadow that chase each other over the billowy fields, the breath of June, the carol of the lark, the dew of night, the wealth of summer, and autumn’s rich content, all golden with imprisoned light’.[xiv]

National Identity

Although Frongoch was the first official Welsh whisky distillery, it is highly likely that illicit distillation occurred before in Wales. For instance, one English newspaper correspondent noted in 1885 that ‘a parochial bird of freedom… suggests that Welsh whisky – an exhilarating cordial distilled from slates – is the national beverage’.[xv] Regardless, there was little question that many Welsh were familiar with more traditional forms of whisky. Indeed, this formed the rationale behind the company’s foundation, as the prospectus stated:

‘Whisky has long been the speciality of Scotland and Ireland, and its production has constituted a very important industry in those countries, whilst nowhere in Wales has such industry yet been established, although the circumstances are especially suitable both in respect of the necessary water and other requirements. The consumption of Whisky [sic] in Wales is very large, and there is no doubt that the article produced in the Principality would command the patronage of its people.’[xvi]

The expectation that Welsh whisky would become incorporated within a wider retinue of Welsh produce, thus gaining a strong domestic market, was not limited to those within the company. For example, it was expected that Welsh whisky would be present alongside Welsh ale, fish, meat, dairy and water in the ‘Royal Welsh Section’ of the 1893 Chester Royal Agricultural Show.[xvii] To outsiders in England, it was easy to presume that ‘Welsh whisky… will be the national drink’, even as late as 1899.[xviii] Yet it appears that Welsh whisky was often excluded from the self-consciously ‘Welsh’ events. Welsh whisky was noted as ‘much talked of… [but] conspicuously absent’ from the 1895 Chester Welsh Society annual dinner.[xix] One year later, a dinner held by the Welsh Land Commission consisted of Welsh fruit, vegetables, meat and fish, but both Welsh wine and whisky were not present.[xx]

In fact, the wider drive for Welsh ‘national’ products was recognised as tenuous and sometimes lampooned with the country. ‘Welsh whisky was followed by Mabon shag and now we have Llwyfo snuff.’ noted one journalist wryly, ‘We are watching the advertisement columns now for Morein cigars, Dyfed rum, and Clwydfardd pale ale.’[xxi] Welsh whisky was also competing with another, radically opposite form of national identity; non-conformist temperance, as sometimes personified in David Lloyd George himself. A non-conformist reverend ascribed the establishment of Frongoch distillery to desires for ‘ill-gotten gain’, dismissing the patronage of the Queen – ‘Pity that a great-grandmother had no more sense’ – and the Prince of Wales – ‘The Welsh Non-conformists… have long since protested against the bad example set by the PRINCE [sic] to the youth of this country’ – in turn.[xxii] Another Welsh ‘patriot’ concluded that ‘Ireland and Scotland… send England poisonous whisky – not pure, unpolluted water’ that Wales produced; a remark that the Western Mail countered explicitly with reference to Welsh whisky.[xxiii]

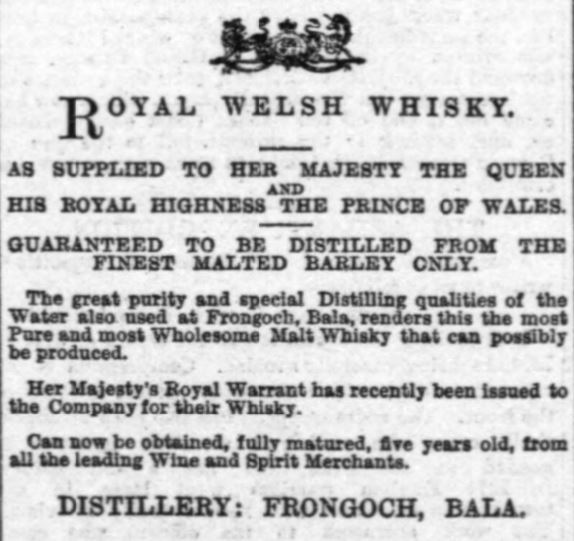

The Welsh Whisky Company arguably had greater success with a second national identity: Britishness. Prior to receiving the Royal Warrant in 1995, Queen Victoria had already visited the distillery in 1891, where she was recorded as being ‘much interested in the promotion of this industry in Wales’; as a consequence, she was presented with a sherry cask of spirit, delivered to Windsor Castle.[xxiv] The Prince of Wales also received a similar gift upon his visit in 1894.[xxv] These visits worked well as initial publicity in England for what one newspaper foresaw as the ‘new Welsh drink invasion’ of 1895.[xxvi] Royal patronage in turn became an integral part of the identity of Welsh whisky, featuring prominently on all advertising of the product.

Source: The Welsh Whisky Co., Advertisement, Western Daily Press (6 Jan., 1896), p. 4

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Reception

Although much noise was made about Royal Welsh becoming the Welsh national drink, the targeted consumer may well have been English. A report from the Dundee Evening Telegraph on the establishment of Frongoch, while potentially biased – it states that ‘the distillery will sell its output as soon as production is begun’, which turned out to be largely untrue – is nonetheless worth quoting at length:

‘Wales is selected for the distillery because the great whisky merchants in England, who find difficulty in getting enough whisky from the best distilleries in Scotland, wish to create a source of supply at the nearest spot to London where the water is suitable. The output of all the best Scottish stills is always ordered years ahead… Hence the desire of the London and Liverpool whisky merchants to have more distillery power at their command, and for economy’s sake they have selected Wales, where mountain water of the proper quality is obtainable, as the nest of their operations.’[xxvii]

In terms of ownership, The Welsh Whisky Co. was not a Welsh company, but rather an English concern located in Wales. Six of the seven directors of Frongoch distillery were representatives of the English wine and spirits industry, with three having interests in distilleries in London and Liverpool; the seventh director, R. J. Lloyd Price, was the director of Corwen and Bala Railway.[xxviii] The majority of the directors were based in London, where the first distillate samples were sent for approval.[xxix] The Welsh Whisky Distillery Co. had an office in 18 Walbrook, E.C. London, while two agents covered North Wales, North & Central England, and South Wales, West & South-West England respectively, with two London-based merchants covering the rest of England.[xxx] Three of the four distributors – E. Young & Co. of Liverpool, J. R. Phillips & Co. of Bristol and Hall & Gray of London – were investors with directors on the board.

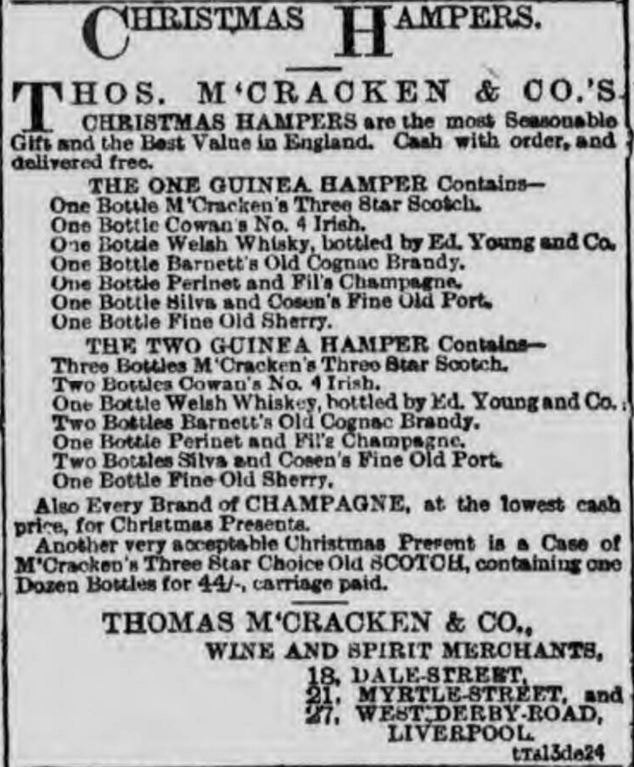

Despite The Welsh Whisky Co.’s strong distribution links with England, Welsh whisky does not appear to have been widely commented on outside of Wales and the border counties. One exception was an early article that alleged distillery refuse had improved the quality of the local fish, which was circulated in Belfast,[xxxi] and Guernsey,[xxxii] amongst others. However, this was more likely related to the numerous pollution cases which were lodged against the whisky industry at the time, especially since the source seems to have been one of the Welsh Whisky Co.’s own directors, Mr. Lloyd-Price.[xxxiii] Welsh whisky, bottled by one of the directors of the distillery, was being included in Christmas hampers in 1892, despite the company’s official embargo on releases until 1895.[xxxiv] The most likely explanation was that this initial release had still not sold out in some areas a full year after dispatch, despite only 600 or 1,200 bottles having entered the market.

Source: Thos. McCracken & Co., Advertisement, Liverpool Mercury (15 Jan., 1892), p. 1.

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

If Welsh whisky received a lukewarm response in England and Wales, the reception in Scotland and Ireland was decidedly frosty. The foundation of Frongoch distillery was described by one newspaper as ‘a very deadly injustice to Ireland’.[xxxv] Meanwhile, the only reference that could be found to Welsh whisky’s reception in Scotland simply read: ‘Scotsmen drugged with bad Welsh whisky.’[xxxvi] There is not any evidence that Royal Welsh whisky was exported from the United Kingdom.

Demise

The Welsh Distillery Co. managed to stagger into the twentieth century, but only just. By April 1900, the liquidator had offered the Frongoch distillery and accompanying buildings for sale at £10,000,[xxxvii] before ultimately being sold for £5,000 to a local man, William Owen. Owen did not succeed in recommencing distillation at Frongoch, although the idea was floated in late 1917, during the depths of the First World War.[xxxviii] A rumour surfaced regarding the resurrection of Welsh whisky in 1925, but nothing appears to have been mentioned thereafter until the late twentieth-century.[xxxix] Nevertheless, although the company was not performing as anticipated, the shareholders had initially planned only to restructure the company, before the excessive compensation demands of the main shareholder, Mr. Lloyd-Price, led to the voluntary liquidation of the company.[xl] When the company was eventually liquidated, the assets of the organisation were sufficient to pay off all debts incurred, although the initial capital of £100,000 could not be returned in full.[xli] As such, the Welsh Whisky Co. was not a complete failure at its point of closure.

After its closure as a distillery, Frongoch underwent a second life as a prison. ‘Large stores’ of bonded stock were recorded to have remained at Frongoch until World War One, when it became a prisoner of war camp.[xlii] Michael Collins, the Irish revolutionary leader, was one of many members of the Irish Republican Army also interned at Frongoch following the Easter Rising, where he spent two years before his release in Christmas 1918.[xliii] In time, Frongoch was eventually nicknamed the ‘University of Revolution’, owing to the study of guerrilla warfare and military manoeuvres which the incarcerated republicans undertook.

Image © St Fagan's National History Museum. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Today, only three bottles of Royal Welsh whisky are still thought to exist, two of which belong to private owners. A wide-ranging collection of material related to Frongoch distillery, including the only bottle of Royal Welsh on public display, donated in 1935 and pictured above, is owned by St Fagan's National History Museum in Cardiff. The museum is undergoing extensive renovation until 2018, but visitors can continue to view their collections by appointment.

Why did Frongoch fail?

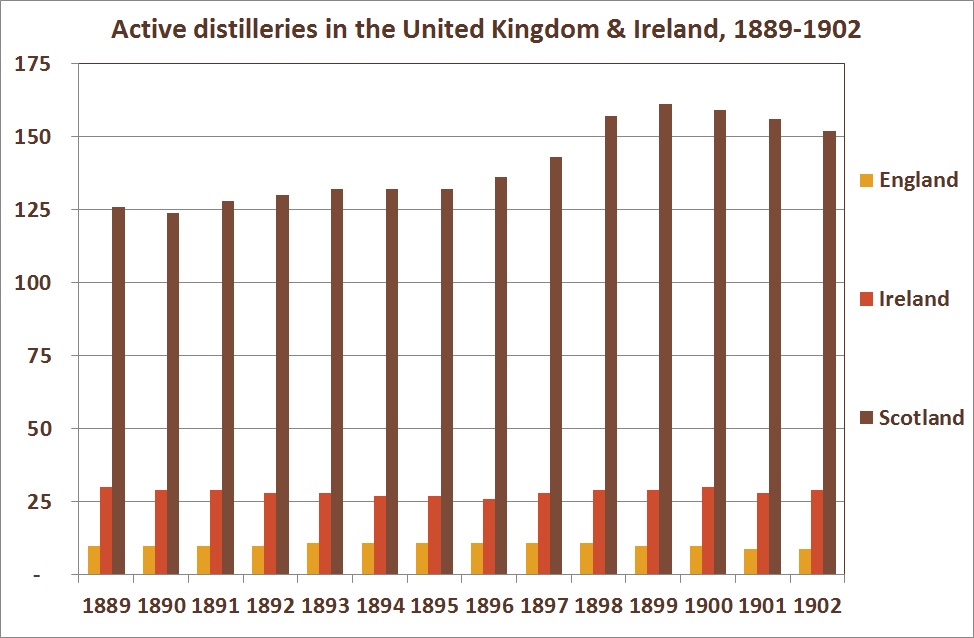

In part, the failure of Frongoch distillery was symptomatic of a wider depression within the whisky industry at the beginning of the twentieth century. Between 1890 and 1900, the number of distilleries in the United Kingdom & Ireland had increased by 37, all of which were located in Scotland. After the Pattison scandal in 1898, the number of active distilleries peaked in 1899, the year liquation of The Welsh Whisky Co. was proposed, before declining again by 10 in the following three years. Some distilleries in Scotland fared far worse: BenRiach was founded in 1898, before closing in 1900 for 65 years. Yet the relative youth of Frongoch distillery alone cannot explain the failure of The Welsh Whisky Company, even among such a period of fierce competition. After all, Wm. Grant and Sons founded Glenfiddich in 1887 and Balvenie in 1892, and these distilleries survived to become two of the top-selling single malt brands worldwide today.

Source: WhiskyInvestDirect via HMRC.

Ultimately, Royal Welsh whisky failed to make the transition from a curiosity to a recognised beverage in the eyes of consumers. In Wales, the provenance of the whisky alone did not seem to sway the opinion of those nationalists fond of whisky. As one contemporary observed, ‘the patriotism of many is not fervid enough to cause them to abandon the old Brig or old Irish for the new compound’.[xliv] Outside of Wales, few seemed to be aware of its existence, despite the deliberate targeting of English consumers. An English correspondent who happened upon the distillery by chance opined that Welsh whisky ‘could not be surpassed, in [his] opinion, by the best blends of either Irish or Scotch’.[xlv] Another brief comment in the Hull Daily Mail simply read: ‘Welsh whisky is quite novel’.[xlvi] In 1900, the year of the company’s liquidation, a visitor for Wrexham was still bewildered to discover Welsh whisky, suggesting, with the faintest of praise, that he was ‘not likely to go to Wrexham solely to sample that stimulant.’[xlvii]

The company itself was aware of this failure. In the annual report for 1898, the directors of the company lamented that ‘they had hoped that the public would support their efforts to place Welsh whisky on the market, but they consider the results disappointing, especially in view of the fact that the advertising has been carried on more extensively during the past twelve months than in any previous period’.[xlviii] This is despite prominent distributors such as Charles R. Haig of London advertising Welsh Whisky as a distinct category alongside Irish whiskey from Dundalk and Scotches such Ardbeg, Ben Nevis and Jura.[xlix]

In fact, the provenance of the whisky seems clearly to have placed Frongoch’s stock at a considerable disadvantage. The final sale of bonded stock only occurred in 1917, a full 17 years after distillation occurred.[l] By way of context, 1917 was acknowledged within the industry as:

‘…the most sensational twelve months ever experienced. The prohibition of distillation, the restriction of clearances, and, above all, the remarkable advance in prices, have combined to make it the reddest of red-letter years.’[li]

That the final stock of Royal Welsh could only be sold in these circumstances may suggest that both blenders and consumers were actively opposed to including Welsh produce in any form into their products, until absolute necessity forced it. This need not reflect the quality of Royal Welsh whisky itself, of which few records remain, nor should we infer that Scottish distilleries themselves were immune from closure – as the interwar decades would show all-too-well – but rather the value placed by the consumer on the whisky being Scotch. It is true that there were suspicions raised at the time that English whisky was being included in Scotch, including in Parliament.[lii] Yet distilleries were producing grain whisky exclusively, whereas Frongoch produced malt alone, which was as expensive as Scottish malt whisky when the distillery was active. While there may have been an economic argument for surreptitiously including English whisky in Scotch, this was not the case for Welsh malt whisky.

The Welsh Whisky Company failed because it had a more difficult task than its contemporaries; namely, to not only convince consumers to try a new whisky, but rather a new category of whisky. Welsh whisky, and world whiskies by extension, had to quickly transition from a novelty to an established spirits category in its own right, in the face of a public that understood whisky as a Scotch or Irish product. There was no obvious attempt made to export Royal Welsh from the British Isles, nor did the whisky succeed in finding a loyal following within it, leaving Frongoch very exposed to any downturns which occurred in the whisky industry, such as that of the late 19th century. Perhaps fittingly, the failings of Frongoch were best summarised by the leading Welsh politician of the day, the future Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. ‘”There was only one Welsh Distillery ever started,” reflected Mr. Lloyd-George, “and it failed because nobody would drink the whisky”’.[liii]

All newspaper articles were accessed through the British Newspaper Archives.

[i] ‘The Welsh Whisky Distillery Company, Limited’, Baner ac Amserau Cymru (19 Jun., 1889), p. 1.

[ii] ‘The Welsh Whisky Distillery Company, Limited’, Baner ac Amserau Cymru (19 Jun., 1889), p. 1.

[iii] ‘Welsh Notes’, The Wrexham Advertiser (18 Oct., 1890), p. 7.

[iv] ‘Local and District News’, North Wales Chronicle (14 Feb., 1891), p. 5.

[v] ‘The Welsh Whisky Distillery Company, Limited’, Baner ac Amserau Cymru (19 Jun., 1889), p. 1.

[vi] Alfred Barnard, The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom (Birlinn Limited, 2008: Edinburgh).

[vii] ‘Llangollen’, The Wrexham Advertiser (19 Dec., 1891), p. 8.

[viii] ‘Welsh Whisky Distillery Company (Limited). General meeting’, The Western Mail (12 Nov., 1892), p. 7.

[ix] ‘Local Finance’, The Western Mail (13 Nov., 1893), p. 8.

[x] ‘Welsh whisky distillery’, The Liverpool Mercury (30 Nov., 1894), p. 6.

[xi] ‘The Metropolitan Regatta’, The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (26 Jul., 1895), p. 6.

[xii] ‘Whisky distilleries of the United Kingdom’, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record (Nov., 1899); Ibid. (Nov., 1900); Ibid. (Nov., 1901).

[xiii] Charles R. Haig, Advertisement, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record (Jan., 1899), p. 1.

[xiv] ‘Wonderful Welsh Whisky’, Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette (25 Jun., 1910), p. 1.

[xv] ‘Holiday notes in North Wales’, The Shoreditch Observer (26 Sep., 1885), p. 3.

[xvi] ‘The Welsh Whisky Distillery Company, Limited’, Baner ac Amserau Cymru (19 Jun., 1889), p. 1.

[xvii] ‘Local News’, The Wrexham Advertiser (25 Mar., 1893), p. 5.

[xviii] ‘Cheltonian Chatter’, The Cheltenham Chronicle (4 Mar., 1899), p. 2.

[xix] ‘St. David’s Day. Celebration in Chester’, The Cheshire Observer (9 Mar., 1895), p. 8.

[xx] ‘A Welsh Dinner’, The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (5 Aug., 1896), p. 5.

[xxi] ‘Wales day by day’, The Western Mail (16 Oct., 1893), p. 5.

[xxii] The Dundee Advertiser (9 Mar., 1891), p. 5.

[xxiii] ‘Wales day by day’, The Western Mail (2 Sep, 1892), p. 5.

[xxiv] ‘Local news’, The Liverpool Mercury (12 Jan., 1891), p. 6.

[xxv] ‘Welsh whisky distillery’, The Liverpool Mercury (30 Nov., 1894), p. 6.

[xxvi] ‘Financial Notes’, The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette (29 Nov., 1894), p. 8.

[xxvii] ‘England wants more whisky’, The Dundee Evening Telegraph (17 Jun., 1889), p. 2.

[xxviii] ‘The Welsh Whisky Distillery Company, Limited’, Baner ac Amserau Cymru (19 Jun., 1889), p. 1.

[xxix] ‘Welsh whisky’, The Western Daily Press, Bristol’ (16 Oct., 1890), p. 5.

[xxx] Welsh Whisky Distillery Co., Advertisement, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record (Oct., 1898), p. 1040.

[xxxi] ‘Trout and whisky’ The Belfast Newsletter (28 May, 1891), p. 6.

[xxxii] ‘Trout and whisky’, The Star (30 May, 1891), p. 1.

[xxxiii] ‘Interesting to anglers’, The Falkirk Herald (18 Apr. 1896), p. 3.

[xxxiv] Thomas McCracken, Advertisement, The Liverpool Mercury (15 Dec., 1892), p. 1.

[xxxv] ‘Vanities’, The Sheffield Evening Telegraph (29 Sep., 1890), p. 2.

[xxxvi] ‘Local sport’, The Western Mail (7 Feb., 1894), p. 3.

[xxxvii] ‘Welsh distillery offered for sale’, The Wine and Spirit Trade Record (Apr., 1900), p. 322.

[xxxviii] ‘Demand for Welsh whisky’, The Western Mail (27 Sep., 1917), p. 3.

[xxxix] ‘The lighter side’, The Nottingham Evening Post (26 Aug., 1925), p. 3.

[xl] ‘Companies and Dividends’, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record (Jan., 1899), pp. 51-53.

[xli] ‘Legal intelligence. In Re The Welsh Whisky Distillery Company (Limited).’, The Wine and Spirit Trade Record (Apr., 1900), p. 348.

[xlii] ‘Spirits removed. Preparing for German prisoners in Wales.’, The Western Mail (12 Dec., 1914), p. 6.

[xliii] ‘Michael Collins: The man and his mission. A personal sketch’. Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencier (24 Aug., 1922), p. 7.

[xliv] ‘Wales day by day’, The Western Mail (13 Apr., 1893), p. 6.

[xlv] ‘Wales day by day’, The Western Mail (20 Sep, 1894), p. 5.

[xlvi] ‘”Mail” Mustard and Cress.’, The Hull Daily Mail (15 Apr., 1897), p. 1.

[xlvii] ‘In Mold and Wrexham. “As others see us.”’, The Wrexham Advertiser (26 May, 1900), p. 3.

[xlviii] ‘Companies and Dividends’, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record (Jan., 1899), pp. 51-53.

[xlix] Charles R. Haig, Advertisement, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record (Oct., 1898), p. 992.

[l] ‘Distiller’s claim for war losses’, Birmingham Daily Post (28 Sep, 1917), p. 7.

[li] ‘Scotch whisky in 1917’, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record (Jan., 1918), pp. 2-4.

[lii] ‘Spirits distilled in England’, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record (Jun., 1903) p. 562.

[liii] ‘The Final Budget’, The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (30 Oct., 1909), p. 7.

Leon Kuebler is Head of Research at WhiskyInvestDirect, the online platform for buying, owning and trading whisky at low cost as it matures in barrel.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.