The Slow Rhythms of Scotch

With exports down to £5.4billion from £6.2bn in just two years, cue panic and 'Scotch on the Rocks!' Before headline writers reach for that well-worn cliché, Tom Bruce-Gardyne suggests taking the long view of this cyclical and remarkably resilient industry …

In late February, a few weeks after presenting Diageo's interim results in London, CEO Debra Crew was in New York, addressing a CAGNY conference of consumer analysts. She conceded there was an ongoing debate on whether the spirits industry's current downturn was cyclical or structural, but hoped to persuade them it was the former. "This is not a new debate," she explained. "Two of my predecessors, Paul (Walsh) and Ivan (Menezes), faced similar questions in prior cycles in 2004 and 2014."

Scotch whisky is an inherently cyclical business. For a start, production can never be fully in sync with the market given the time-lag between distilling the grain, ageing the spirit and finally bottling the whisky. As a rough industry average for malts and blends combined, it is currently around 7-8 years - plenty of time for the world to flip on its head as US President Trump has proved in a matter of months.

Trying to forecast future demand with some degree of accuracy is all part of managing a brand and helping the industry navigate periods of feast or famine. It is a fiendishly difficult task, but distillers have definitely got better at it.

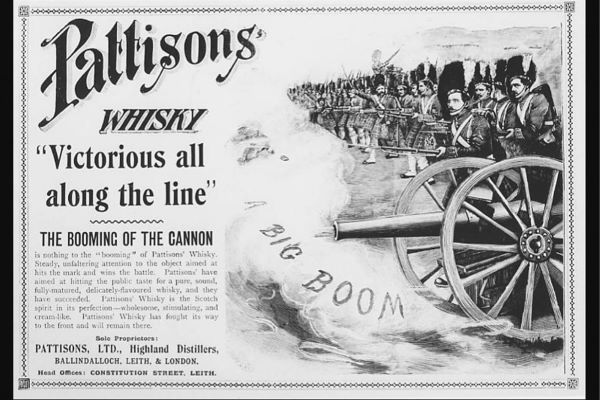

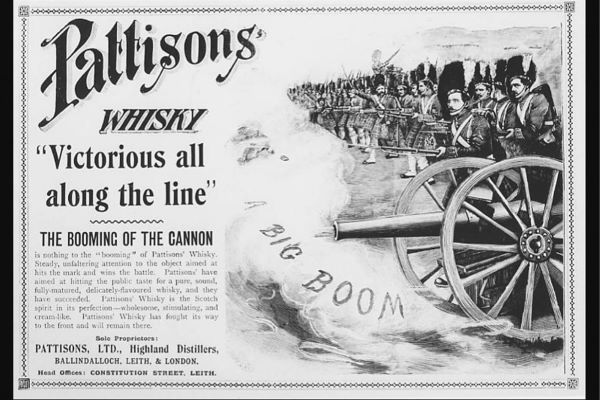

The first great whisky boom-to-bust in the 1890s was largely self-inflicted. Like America's sub-prime mortgage market pre-2008, the late Victorian whisky trade was drunk on credit. This funded a mad building spree on Speyside, with a rash of new distilleries just as the original whisky loch was filling up. From 2 million gallons in 1892, warehoused stocks soared to 13m gallons in just six years and soon after this classic speculative bubble burst.

One of the biggest blenders, Pattison's of Leith, collapsed, bringing others down in its wake. While the brothers Pattison languished in gaol for fraud and embezzlement, the industry crawled into the 20th century with a terrible hangover. It soon faced an existential threat from the taxes of teetotal chancellor, David Lloyd George. The silver lining was that it forced distillers to export giving Scotch a lead over rival spirits it has never lost in terms of its global footprint.

After suffering US Prohibition and the Depression, Scotch began its long post-war golden age that took exports from 60m lpa (litres of pure alcohol) in 1960 to 161m in 1970, and to 250m in 1980. Value jumped from £65m to £746m over the period. Confidence gave birth to complacency that growth was guaranteed, that Scotch would keep fuelling the American Dream, and keep surging ahead in Japan, Venezuela, Spain, Italy, South Africa … you name it.

In hindsight it feels the industry ploughed on with its eye in the rear-view mirror. The past decade's growth was extrapolated to predict the future. The result was a whisky loch that took many years to drain, and caused a terrible cull of distilleries in the early 1980s. It was a grim decade of redundancies and three-day weeks.

This January, when Brown-Forman announced it was scaling back production and cutting jobs at Glenglassaugh and BenRiach, it felt like déjà vu. Warehouses have been filling up across Scotland and demand has been dropping, or 'normalising' to use the industry's preferred euphemism. It's no secret that a number of new distilleries are struggling to keep afloat. So, are we back to the 1980s?

The short answer is 'No', but to understand why we need to explore some of the causes for what happened forty years ago. The industry's big white whale – the Distillers Company (DCL) was badly run. Its whiskies like Dewars, White Horse and Johnnie Walker competed as separate fiefdoms, while outside competition was choked off at home by holding prices down deliberately. Overseas, particularly in the US, Scotch brands were snuggling down with their ageing consumer base, and failing to recruit new drinkers who were succumbing to the charms of Smirnoff and Bacardi. This was equally true of other whisk(e)ys from Tennessee to Tokyo.

With so much capital tied up in stocks, the Scotch industry was particularly vulnerable to high interest rates in the UK. These had been hiked to 17% by the Conservatives in 1979 to tackle inflation, and averaged 12% throughout the 1980s.

The writer Nick Morgan, who spent thirty years at Diageo, traces the whisky loch to DCL's decision to pull Johnnie Walker Red Label from the UK, where it had been selling 1.25m cases a year. It followed a dispute with the European Commission, and "left the company sitting on more than eight years' worth of inventory that had been set aside to provide for the brand growing in the home market alone at 15% a year," he wrote in Barley magazine.

As well as culling over a dozen distilleries including some that came back like Port Ellen, the DCL sought to drain the loch by dumping bulk blends on markets like France. Volumes eventually recovered, but margins took a lot longer to repair. The fact that supply outstripped demand was obvious from the UK supermarkets where own-label Scotch had 40% of the market in 2001, with prices down to just £7.49 a bottle.

Back then no-one in the industry spoke of premiumisation, but for over a decade they have talked of little else. For those who have known only the good times, the current downturn must feel deeply worrying. For those who take the long-view, there is comfort in the resilience of Scotch whisky. It's been here before and will be here again.

Award-winning drinks columnist and author Tom Bruce-Gardyne began his career in the wine trade, managing exports for a major Sicilian producer. Now freelance for 20 years, Tom has been a weekly columnist for The Herald and his books include The Scotch Whisky Book and most recently Scotch Whisky Treasures.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.