Scotch rules, OK? The pros and cons of Scotland's tight whisky regulations

We’ve been locked down for long enough – it’s time to set us free. This cry for release from captivity, which can still be heard in ‘stay at home’ Scotland, echoes a much older debate around Scotch whisky, writes Tom Bruce-Gardyne for WhiskyInvestDirect.

When it comes to whisky, Scotch's rules are much more comprehensive than those of other whisky producing countries.

Some say the spirit’s notoriously strict rules on production and labelling are suffocating creativity and innovation. And that the only beneficiaries are those making whisk(e)y in Ireland, Japan or North America where things are more relaxed.

If you want to know how relaxed, grab a copy of ‘Alt Whiskey’ by Darek Bell, co-founder of Nashville’s Corsair distillery. It reads like a wildly alcoholic cookbook with recipes for Pumpkin spiced moonshine, Hop Monster single malt and even Cannabis whiskey.

Never in a million years would the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA), who police the industry, consent to any of those. In Scotland the only permitted additive to cereal grain, water and yeast, is spirit caramel to stabilise the colour – anything else, and the hallowed name of ‘whisky’ must go.

As a result the industry could only watch from the side lines as Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Honey built a whole new category that began to challenge the scale of blended Scotch in the US. Some tried it on with range extensions classified as ‘spirit drinks’ like Dewar’s Highlander Honey which was quietly withdrawn a few years after its launch in 2013, presumably because it never caught on. Others have included William Lawson Spiced and the lime peel-infused Ballantine’s Brasil, but in the main the industry has obeyed the spirit of its own laws.

The Irish see it as an own goal. “Blended Scotch is a declining category but makes up 85% of the industry – and this is partly because rigid regulations imposed by the SWA stifles innovation,” claims John Teeling, CEO of the Great Northern Distillery and co-founder of the Irish Whiskey Association.

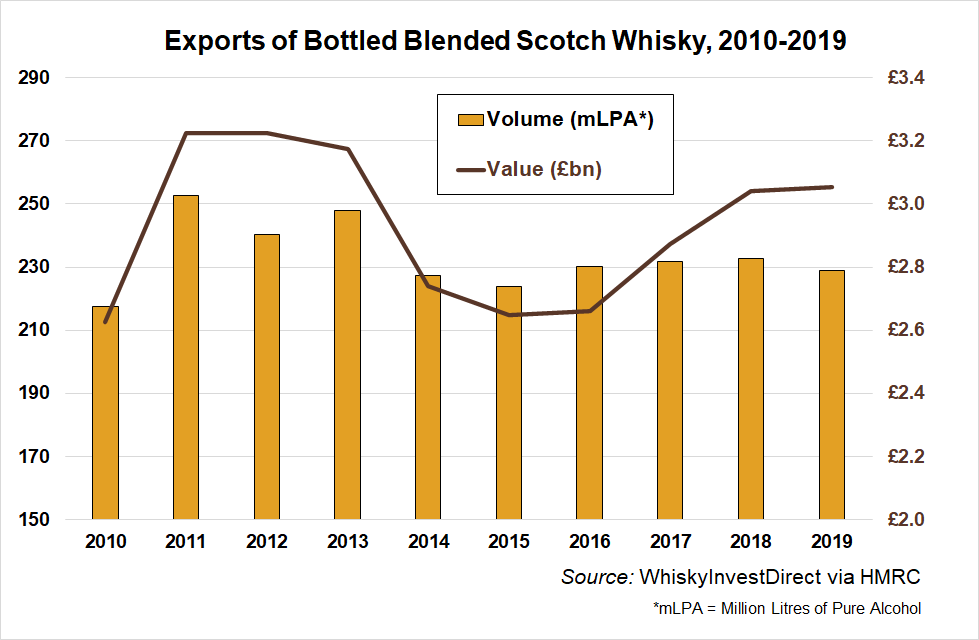

In truth bottled blends are holding their value at £3 billion last year and are growing at the premium end. Nevertheless, there is an acceptance that Scotch must keep evolving. Dr Jim Beveridge OBE, Johnnie Walker’s master blender, says: “there has to be room for some degree of innovation - Scotch can’t afford to sit still.”

But while there is evident frustration at times at the constraints of these self-imposed rules, the question is whether it is a price worth paying for the way they protect the integrity and good name of Scotch whisky.

Take the issue of new distillers for example.

In Scotland you cannot create a blend to build the brand name of your distillery as you wait for your first whisky to be released. You can, however, in the United States and Ireland where it appears to be the accepted business model. By name, the Portmagee Distilling and Brewing company in Kerry, might suggest a pair of stills bubbling away in the background. In reality that’s just an aspiration and its 9 year-old Portmagee whiskey – said to reflect ‘Kerry and the wild Atlantic way’ – is actually produced by Great Northern in Dundalk on the Irish Sea.

In a similar vein, MGP of Indiana supplies countless American bourbons, including George Dickel and until recently Diageo’s Bulleit brand. While many are upfront about their origins others are more circumspect, and in 2015 the MGP-supplied Templeton Rye had to settle a class-action lawsuit for ‘deceptive marketing’, with the bill estimated to reach as much as US$2.5 million.

As with Irish would-be distillers, the issue is not about quality so much as transparency which will impact the Irish whiskey tourism industry set to attract 1.9 million visitors by 2025. “With people coming to distilleries that don’t exist you do have a problem because then ‘it’s a plague on all your houses,” says Peter Mulryan co-founder of Ireland’s Blackwater distillery.

When it comes to unscrupulous behaviour the Scots were once ten times worse and thought nothing of shipping raw Scotch to Dublin to have it reshipped as bonafide Irish whiskey (though in fairness that was back in the late 19th century). The practice continues today with Japan, whose whisky industry is in desperate need of tighter regulations to stop widespread abuse. Cheap bulk whisky flows in from Canada and other places to be bottled as Japanese whisky and sold for many times the price in markets like the USA, all perfectly legally.

Back in Scotland, Paul Miller, founder and CEO of Eden Mill distillery & brewery, complains that “the current rules suit the big companies who can often experiment with their Irish, Japanese or American whiskeys and leave Scotch alone, leading to missed opportunities through a lack of innovation.”

He may have a point, but on balance it seems better to have a little too much regulation than too little. Whether that applies to our current woes and any easing of the lockdown, remains to be seen.

Award-winning drinks columnist and author Tom Bruce-Gardyne began his career in the wine trade, managing exports for a major Sicilian producer. Now freelance for 20 years, Tom has been a weekly columnist for The Herald and his books include The Scotch Whisky Book and most recently Scotch Whisky Treasures.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.