Scotch Whisky's Bicentenary

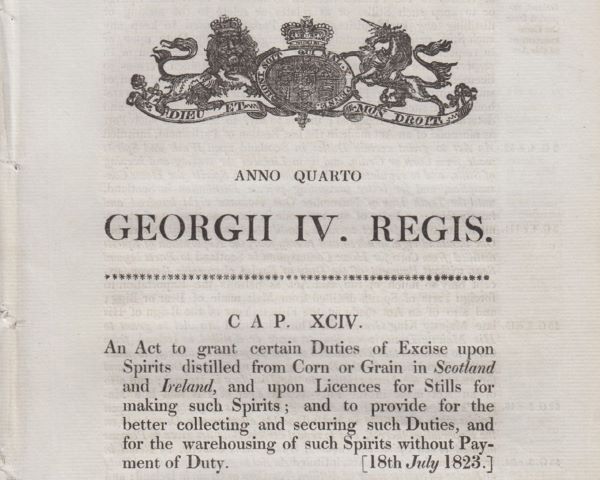

Some big single malts have a very special birthday this year, but as it all stems from the Excise Act of 1823, it should be an industry-wide celebration argues Tom Bruce-Gardyne …

Last night the circus came to town, or rather to a field in Speyside, as part of The Macallan's big birthday celebrations. Not an old-style circus with clowns and lion tamers I hasten to add, but a spectacular show full of immersive story-telling and acrobatic high jinks performed by the Cirque du Soleil at the distillery for the next three weeks. The famous whisky has been telling the world it is '200 years young'.

"2024 marks a momentous year for The Macallan as it celebrates its bicentennial," says the brand's creative director, Jaume Ferràs who talks of: "Bridging the gap between the art of whisky making and the spectacle of performing arts, creating an unforgettable experience that is deeply rooted in the nature that surrounds us at The Macallan." Tickets cost £200 and, as I write, there are still a few available.

In truth, it is not just The Macallan or those other distilleries founded in 1824, such as The Glenlivet, Fettercairn and Cardhu that should be marking the occasion. It is really a belated birthday for the entire industry, which, to a large extent, owes its very existence to the Excise Act of 1823.

Arthur Motley, MD of the Dormant Distillery company, owners of Royal Mile Whisky, is convinced the Act was the big bang moment for Scotch. Having studied all of its 51 pages in depth, he says: "It was not preordained that Scotland would become a successful whisky-making nation."

Whisky books have tended to view the Excise Act purely in terms of tax, that by lowering the charge for a running a still to £10 a year, it encouraged an army of illicit distillers to come in from the cold and take out a licence. But there was a lot more to it than that as Arthur and his fellow whisky historian friend, the writer Dave Broom, have discovered.

The powers that be had repeatedly tried to impose order on chaos, but their efforts to stamp out moonshine and staunch the leaks in the tax revenue had failed miserably. 1823 was a last-ditch attempt, and they were determined to get it right this time. In effect, the authorities wrote the manual for how Scotch malt whisky was to be produced and, in doing so, created a blueprint for what a distillery should look like.

The Act was incredibly prescriptive right down to how every pipe, every vessel and every still was to be connected. For those modern-day distillers who complain about the restrictive nature of Scotch whisky regulations stifling innovation, it all started here. But it is worth remembering what the whisky business was like before 1823.

On one side you had thousands of small pot stills in the Highlands and Islands feeding a supply chain controlled by criminal gangs who were not averse to using extreme violence for all the romance around illicit whisky. And on the other, you had what was left of the drink's first attempt to create an industry in the Lowlands.

To start with, these early industrialists were mainly concerned with supplying London with a base spirit that could be rectified into gin. The tax system had compelled them to run their small, flat-bottomed stills at a ferocious pace. Instead of carefully separating the good alcohols from the bad by collecting the middle cut, it is likely they would have collected everything. Demand for this filthy spirit might have endured among the most desperate in society in Scotland, but it was hardly whisky you could export, let alone one day sell for millions in a Lalique decanter like the most rarified expressions of The Macallan or Dalmore.

The Excise Act helped a tiny handful of the late 18th century distilleries like Bowmore and Oban to survive, and encouraged many more to join them and invest in a sustainable business. A business that now supports 66,000 jobs in the UK and, as of 2022, contributed £7.1 billion to the UK economy.

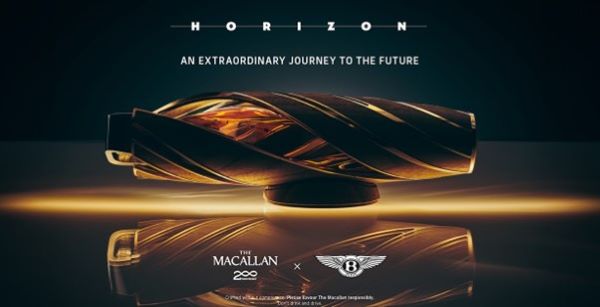

The 200th birthday celebrations include lots of 'limited releases' from the distilleries concerned. There is everything from a 'special release' 12 year-old Glenlivet for £55, to The Macallan Horizon at £40,000 – a tie-in with Bentley that comes lavishly packaged. In the breathless purple prose of its website: Its 'aluminium ribbon … envelopes the glass vessel, while the finest low carbon leather, in a chestnut hue, ensures protection and sophistication.'

Rather more down to earth, Fettercairn is having a party in late July for its "personnel and their families, along with members of the community and people who have helped the distillery," says its manager Stewart Walker. "There'll be beers, music and a barbecue."

He feels able to predict reasonably confidently that "we might still be here in 200 years from now. Fifty years ago, I don't think you could have said that with confidence." He credits his team, the quality of the whisky and an enlightened owner "willing to invest and who has a great belief and confidence in the brand."

Award-winning drinks columnist and author Tom Bruce-Gardyne began his career in the wine trade, managing exports for a major Sicilian producer. Now freelance for 20 years, Tom has been a weekly columnist for The Herald and his books include The Scotch Whisky Book and most recently Scotch Whisky Treasures.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.