Blends vs. Singles and the 'Curse of the 12' in Scotch Whisky's Deluxe US Market

Higher-priced brands now outsell all cheaper Scotch whisky in the USA. Age statements still matter, but single malts are growing fast, reports Tom Bruce-Gardyne for WhiskyInvestDirect...

WITH the EUROs dominating the airwaves, Mathieu Delandes, marketing director at Ballantine's and Royal Salute, sees a parallel with Scotch and the old debate between blends and malts.

"If I was doing a football analogy, taking a very good player or a very good whisky, if they are not able to play together, there's an issue."

The solo star being the single malt while the blend is the team.

Royal Salute is the quintessential super-premium blend with nothing bottled under 21 years. It sits at the upper end of what used to be called 'deluxe blends' of 12 year-olds and above that is still led by Johnnie Walker Black Label and Chivas Regal.

It was into this world that William Grant's Glenfiddich barged its way in the 1970s, offering a new vice called single malts.

"Global travel retail is a key channel for this kind of category, and obviously we have been negatively impacted by Covid and people not being able to travel," says Mathieu. With his bosses at Pernod Ricard reporting a 57% drop in travel retail sales in the second half of last year, that may be an understatement.

However, on the ground "in China, Japan, most Asian markets and even the US, the situation has been very positive," he says. "There has been a transfer of consumers buying at airports to buying locally."

A fundamental aspect of these whiskies, at least traditionally, is having a double figure age-statement proudly displayed on the label. "I think it's a universal language," says Mathieu.

"Numbers are simple to understand, and not all our consumers are experts. Age is an important marker for them to know where the whisky sits in the hierarchy. Especially with 21 and above, if you consider your life and what happened 21 years ago – that's a lot.

"I think there's a kind of magic and mystery in such a long age-statement, and that's true across every market and every generation."

Last September, Ballantine's – the number two Scotch after Johnnie Walker – added a 7 year-old to its range, to sit between Ballantine's Finest and a raft of older expressions from 12 to 30 years old.

"It's proved to be very successful, and I think reinforces how much age helps in understanding the sense of 'more premium than' or 'more sophisticated than'," says Mathieu.

"It helps explain why it's more expensive."

But tying up stock for these old blends is a huge burden for distillers, and industry insiders have been known to grumble about the so-called 'curse of the 12'. You would doubt Diageo would ever remove the 12 from Johnnie Walker Black, but there is no number on its Double Black lookalike, nor the glitzy Blue Label that has become the go-to 'status' whisky in the range.

"In Baghdad it had to be Johnnie Walker Blue," says a husky-voiced US intelligence officer at the start of the brand's lavish, full-length documentary – The Man Who Walked Around the World – that came out in November.

You can see Diageo's logic in trying to wean consumers off numbers onto colours, and plenty of pundits question how Scotch whisky age-statements create a hierarchy based solely on a belief in 'the older the better'.

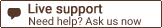

Yet for all its imperfections, a number on the label does actually mean something, unlike all those clichéd marketing terms like 'small batch' or 'limited release'. And these well-aged whiskies are in the right price bracket for a wealthy market like America. They sit in the upper two tiers – 'high-end premium' and 'super-premium' – which have grown by 37% in the past decade to just over 5 million cases in each of the last 3 years, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the US.

Indeed, the top 2 tiers have now out-sold the cheaper end of the market every year since 2017 by volume – 2020's Covid Crisis included – and accounted for 3 times as much by value last year.

These brands are aspirational, unlike the sea of standard blends filling the bottom two tiers that have halved over the period. But their weakness in the eyes of many whisky-drinkers in markets like the US is that they are blends, not single malts.

In 2017 Pernod Ricard sought to blur the distinction by launching a range of three single malts under the Ballantine's label to highlight the role Glenburgie, Miltonduff and Glentauchers play in the blend. "The fact the brand was considered credible to move into malts shows it's not just about malts or blends," says Mathieu Deslandes.

But the popular perception that malts are better than blends is proving remarkably hard to shift, and if you have any suggestions the Scotch whisky industry would love to hear from you.

Meanwhile, as though to prove that blends can be better if the constituent parts are playing as a team, there's the awful memory of what Iceland did to England in the last Euros in 2016.

Award-winning drinks columnist and author Tom Bruce-Gardyne began his career in the wine trade, managing exports for a major Sicilian producer. Now freelance for 20 years, Tom has been a weekly columnist for The Herald and his books include The Scotch Whisky Book and most recently Scotch Whisky Treasures.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.