Scotch by numbers: How much do age statements matter in whisky?

If you've been around as long as Scotch whisky, age can be a sensitive subject reports Richard Woodard for WhiskyInvestDirect. And while some brands declare theirs with pride, others are more coy...

WE HAVE an obsession with knowing the age of things.

Our understanding of people, buildings, cars or antiques isn't complete until we put a number to them and attach a few value judgements as a result.

But what about whisky? Does age matter?

The simple answer is: yes. You can't call Scotch whisky Scotch whisky until it's been matured for three years and a day, and everyone expects to pay more for a 40-year-old single malt than for a 10-year-old.

But with a subject as multi-faceted as whisky, the complete truth is less straightforward.

There are three main approaches to age in whisky.

- There's the 'conventional' use of age statements – often beginning at 10 or 12 years old, and ascending from there: 15, 18, 25 and so on.

- Then there's no age statement (NAS) whiskies that eschew numbers for other ways of selling themselves.

- Thirdly, there's the young crowd, often new distilleries releasing youthful whiskies to serve a dual purpose: satisfying the curiosity of whisky enthusiasts and bringing much-needed revenue to a fledgling business as its whisky matures.

Whisky is bloody complicated. There are so many permutations in its production process – raw materials, fermentation, distillation, maturation – that, from the cask, some 12-year-old whiskies still taste relatively 'raw', while others seem older than their years.

The art of the blender is to reconcile these differences in order to create a coherent, consistent and balanced liquid that delivers what the consumer wants, at a price they are willing to pay.

Deciding what number to put to this art-cum-science is an approximation, and one often dictated by market forces and consumer expectation. The prevalence of 12 years old as a benchmark of maturity owes much to the rise of premium blends such as Johnnie Walker Black Label and Chivas Regal, which prompted similar moves from the pioneers of the modern era of single malt.

Glenfiddich's core expression is now established as a 12-year-old, but it has been both an 8-year-old and an NAS whisky in its time. When stablemate Balvenie was launched as a single malt in 1973, it too started off as an 8-year-old.

And there are always exceptions to any rule. In the 1970s, Italy was the world's largest market for single malt, thanks to the opportunistic success of Glen Grant 5-Year-Old (in turn prompting others to bottle 5- and 7-year-old malts for the market). But this was single malt competing head-on with blends, rather than operating at a premium in pricing terms. And how many consumers understood – or cared – that they were drinking single malt in the first place?

If age statements are a useful but imperfect signpost for consumers, they're also quite a bind for whisky makers. Because if you're putting together the blend for Johnnie Walker Black Label or Glenfiddich 12, every drop of that liquid has to be matured for at least 12 years – which is quite a commitment in terms of production and long-term planning.

NAS frees the whisky maker from those constraints and, in a perfectly meritocratic world, not having a number on the label wouldn't matter if the whisky were good enough. But although NAS has always been with us, and although the category includes some of the world's most successful whiskies (Johnnie Walker Blue Label, anyone?) it doesn't always inspire consumer confidence.

In 2012, Macallan launched the 1824 series – four NAS single malts called Gold, Amber, Sienna and Ruby – that aimed to use colour, not age, to communicate flavour and quality. The move was much criticised by whisky enthusiasts, who suspected the cynical manipulation of constrained stocks, and the range was axed in 2018 in favour of a trio of 12-year-old age-stated malts.

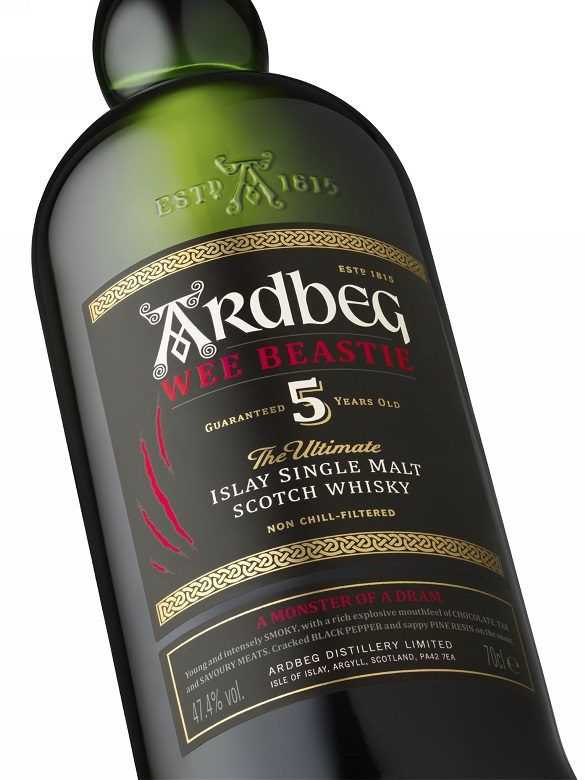

Brendan McCarron, head of maturing whisky stocks at Glenmorangie and Ardbeg, has a role in making whiskies that sit in all three of the age camps: age-stated, NAS and – among the 'youthful' group – the recently launched Ardbeg Wee Beastie, with a 5-year-old age statement.

"There's nothing wrong with age being used to work out something," he says, "but the flipside when you make NAS whisky is that sometimes we're sourcing very expensive casks that we're only using once and then selling on.

"So an NAS whisky can be considerably more expensive than an age-stated whisky."

For all the success of NAS whiskies such as Glenmorangie Signet or Ardbeg Uigeadail however, McCarron can't imagine abandoning the 10-year-old age statement for flagship expression Glenmorangie Original. And despite all the many variations and exceptions, he still thinks single malt tends to hit a 'sweet spot' at 10-12 and 18 years old.

"This idea that age equals quality is a conversation started by the whisky industry," says McCarron. "Now there's been a bit of a swing the other way. Age isn't the only thing, but to say that age does not matter is also incorrect.

"I do not believe that I could make a whisky like Glenmorangie 18 Year Old without waiting 18 years."

Richard Woodard has been writing about spirits and wine for 20 years, editing and contributing to a number of magazines and websites, including Decanter, The Spirits Business, just-drinks.com and Club Oenologique. He was also one of the founding editors of Scotchwhisky.com.