Putting Scotch on the Map

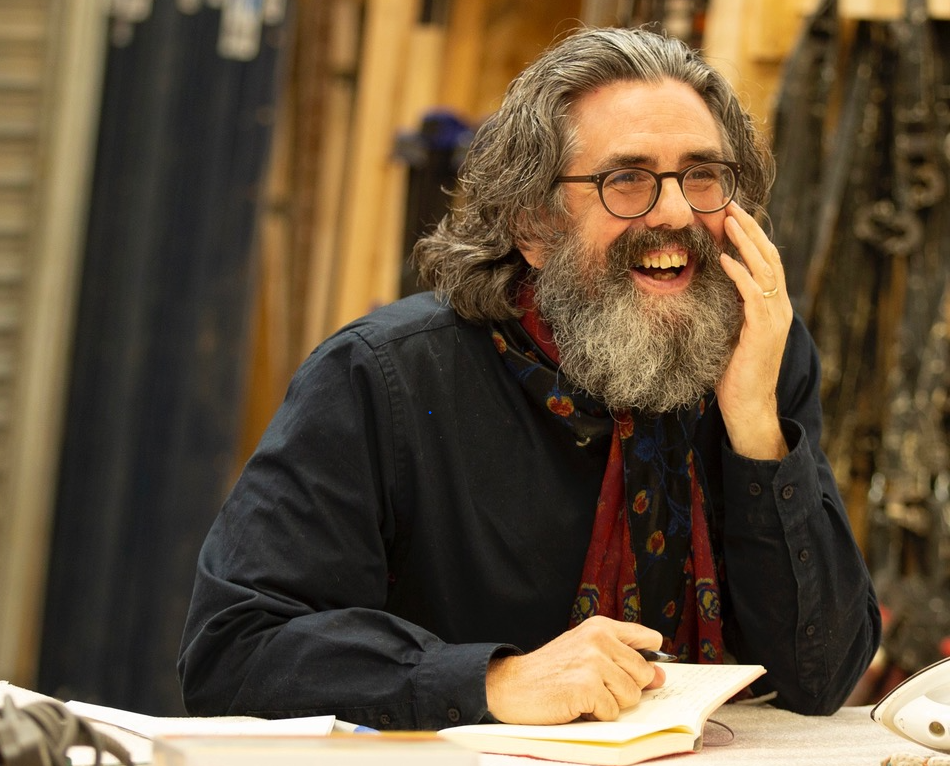

What makes Scotch whisky unique is not its production process or ingredients, it is its provenance and the people who make it. This is the subject of Dave Broom's new book which he discusses with Tom Bruce-Gardyne...

The days when those two words 'Scotch whisky' were all but synonymous have long gone. Scotch now swims in an ever-widening sea of whisk(e)y from North America, Ireland and Japan along with a growing profusion of 'world whiskies' from everywhere else. And that's not to mention the biggest category of all, depending on your definition – Indian whisky.

To maintain its position in this crowded space, the drink relies on provenance and the richness of its backstory.

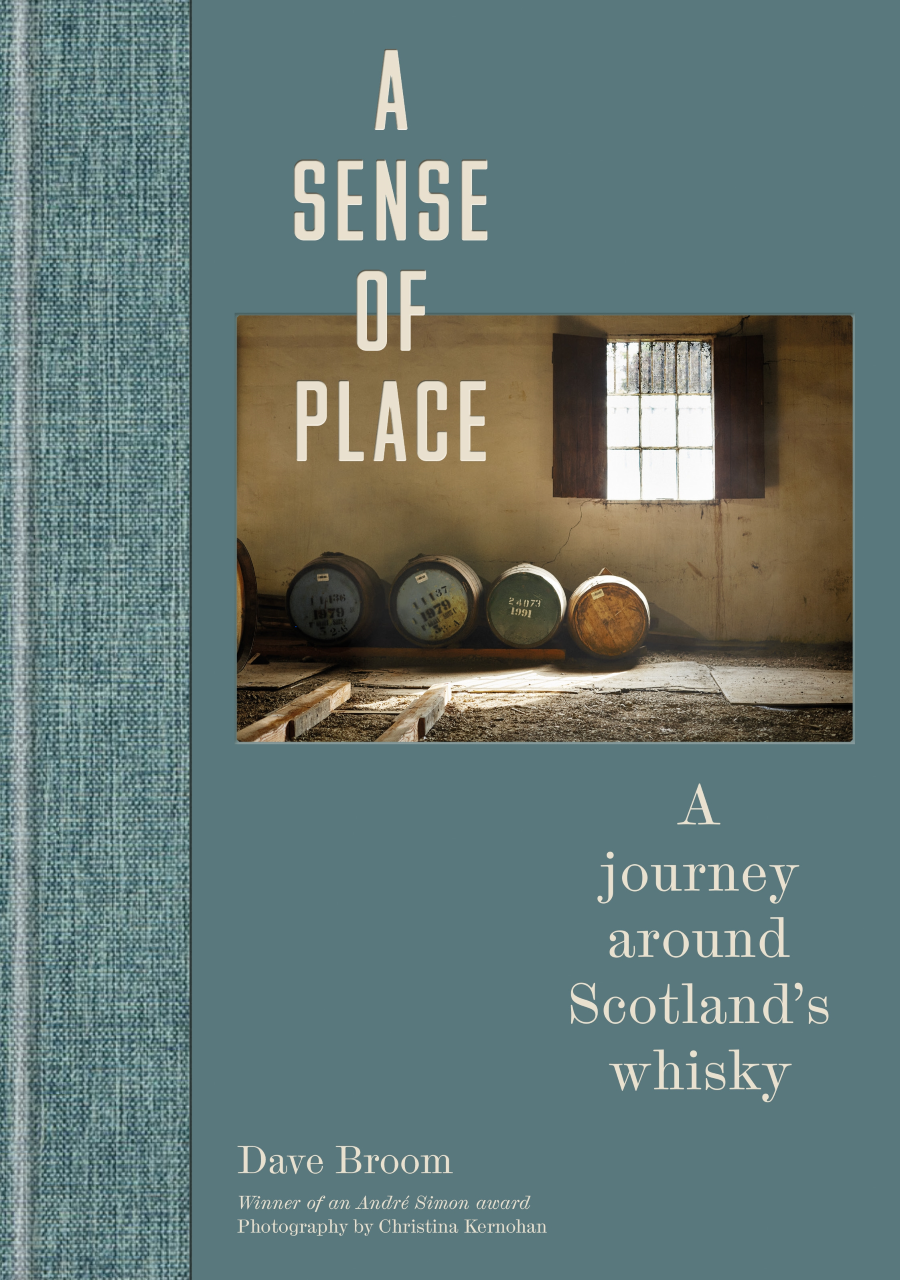

As David Robertson, co-founder of Edinburgh's Holyrood distillery once told me: "It's the history, heritage, landscape and knowhow behind Scotch whisky that gives the spirit its added value." This brings us to a rather beautiful book just published by the acclaimed whisky writer, Dave Broom.

'A Sense of Place' is a meandering journey around Scotland, visiting distilleries large and small to gauge how much they truly reflect where they're from. For Broom, this notion of 'place' comes down to conditions, initially.

"Scotland's geology and climate dictate that barley grows here, and therefore whisky is made here," he says. "Then, there's the fact it's been made for a long time, and is embedded within community and culture. And I think craft and skill, and sustainability are also part of place."

For him, a word like terroir which the French use to defend the uniqueness of Champagne for example against all the sparkling wines made in its mirror image, is too narrow to apply to Scotch. It misses the human element.

As to how much of this 'sense of place' you can pick up in a dram, well that's bound to vary and is obviously subjective. In discussing Ardnamurchan, a small, west coast distillery he's particularly fond of, he writes: "The fact that it is from here is what matters. The fact that it also tastes of here is a bonus."

By contrast the sheer scale of Glenfiddich causes doubt. "Can place exist in here?" he wonders. "Provenance, heritage and place are vital elements for single malt, yet large distilleries with their computers can seem oddly detached, rootless places." In the end, despite its ability to pump out a staggering 23 million LPA per year, enough to fill around six million cases of whisky, it seems that Glenfiddich passes the test thanks to the people who make it.

But what of blended Scotch? "People relate to provenance, so single malts work. Blends are stateless, global brands," he writes on his way to visit the Johnnie Walker blending team. "Is place important to blends, and if so, did it come from the early days when the grocers utilised local whiskies?" The question is left hanging in the air.

Johnnie Walker's owners could have shut down many more malt distilleries than they did in the 'whisky loch' years of the 1980s according to Dave Broom. For a business with very little interest in single malts back then, he says: "There was pressure from the accountants, who were saying 'why don't we just build one big distillery in Grangemouth?'." It would certainly have been cheaper.

He credits the late Turnbull Hutton, the firm's head of distilling in Scotland, for fighting to keep the lights on. "Turnbull was no romantic, but there were distilleries that could have, and maybe should have closed because of the surplus stocks at the time. Yet the workers were retained and paid because he identified there is a moral responsibility on the part of the owner to that workforce and that community."

The company then called United Distillers, now Diageo, launched its six 'Classic Malts' in 1988, each representing a whisky region. This gave people a way in to single malts, just as putting grape varieties on labels had done for wine.

Broom agrees about the importance of having signposts for new consumers, but is not really a fan of this regional approach. "The problem I've got is that it doesn't actually hold up to any intellectual scrutiny," he says, pointing to the vast distance between Glengoyne and Wolfburn that are both 'Highland'. While Dufftown in Speyside has six distilleries that, in his view: "all make incredibly different new-make spirit."

Describing these whisky regions as "overmarketed", he advocates using flavours like 'spicy', 'rich' or 'smoky' instead. Whether brand owners could ever agree on the meaning of 'rich' is another matter, while inevitably some cannot resist covering all the bases by describing their whiskies as 'rich, spicy, smooth, fruity … and infused with a subtle hint of smoke.'

At the end of the journey, Broom concluded that: "The Scotch whisky industry is in a good place. I came out of it with greater optimism than perhaps I went into it, and I was inspired by a lot of the newer distilleries. But talking to the people who make it and hearing of their identification with community and place, I would love that story to be front and centre in marketing campaigns rather than spurious history."

Scotch whisky's sense of place is all important – it is what defines the drink. In teasing out some of its many stands, this book tells that story brilliantly. Could marketing folk do a similar job? I have my doubts.

Award-winning drinks columnist and author Tom Bruce-Gardyne began his career in the wine trade, managing exports for a major Sicilian producer. Now freelance for 20 years, Tom has been a weekly columnist for The Herald and his books include The Scotch Whisky Book and most recently Scotch Whisky Treasures.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.