How to survive a century in the whisky industry

How quality, output & corporate structure decided the fate of Scotch distilleries since 1905...

SINCE the turn of the millennium, the Scotch whisky landscape has witnessed a revolution, writes Leon Kuebler for WhiskyInvestDirect.

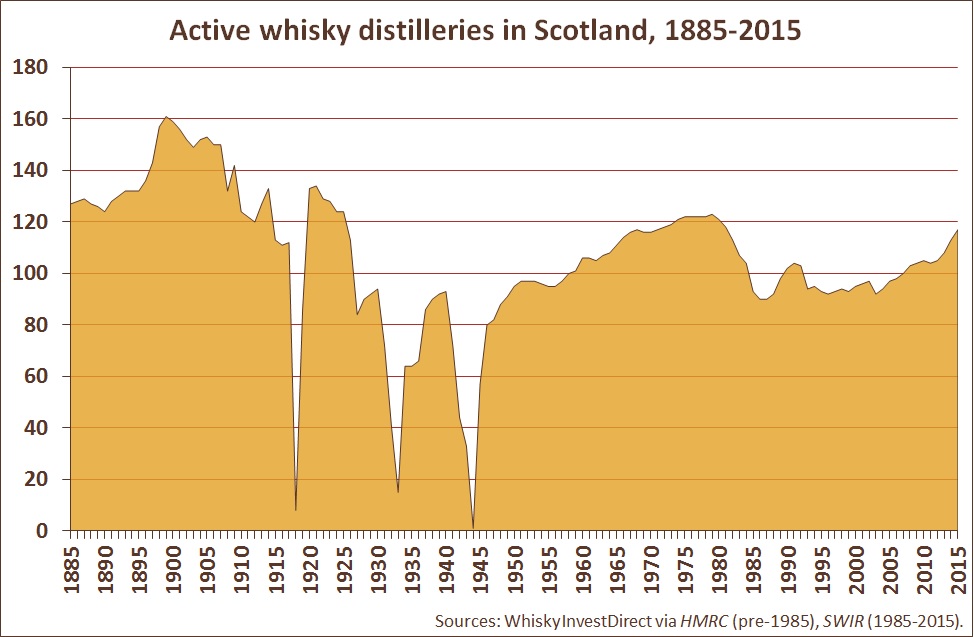

After two decades where distilleries were as likely to close as start (or resume) making whisky, the number of active whisky distilleries has risen steadily over the last 15 years.

On the one hand, established giants such as Diageo, Pernod Ricard and William Grant have been busy constructing mega-distilleries; on the other, the American craft distilling phenomenon has crossed the Pond, spawning many micro-distilleries with minute production capacities across Scotland. Closed distilleries such as Glencadam and Glen Keith have been resurrected, while new malt distilleries have begun to spring up across the globe.

The emergence of a new distillery is thrilling for both consumers and producers, even if it requires immense effort to accomplish. Yet once a distillery has been established, the next question is: how long will it last?

As of 2015, there are 117 distilleries producing whisky in Scotland – a number approaching the post-war peak of 123, set in 1979. If you discount the three catastrophes of the twentieth century – the two World Wars and the Great Depression – Scotland has generally had around 100 or more distilleries producing whisky in any given year since accurate records began. In most cases, external factors have therefore not been the cause behind mass closures of whisky distilleries.

In November 1905, The Wine & Spirit Trade Record published a supplement, entitled ‘Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom’. This supplement, which proudly states that it ‘circulates amongst Distillers, Blenders, Brewers and Wine and Spirit Merchants of the United Kingdom and the Colonies’, lists the distilleries active that year in Scotland, Ireland and England, along with their proprietors and (where available) the prices of new make spirit produced that year. As such, it provides an invaluable insight into the industry as it was over 110 years ago.

There were 152 distilleries producing whisky in Scotland in 1905. This was a slight decline from the all-time peak of 161 distilleries active in 1899, but represents a level which has not been surpassed since.

Of the 149 dedicated malt distilleries operating in 1905, only 79 survive today – although two of these distilleries, Glengyle and Annandale, did not exist for the majority of the twentieth century and thus bear little resemblance to their namesakes.

Grain distilleries were far less likely to make it into the twenty-first century, as only Cameronbridge and North British are still in production of the 11 grain distilleries active in 1905. The situation for those distilleries producing both malt and grain was worst of all; Saucel, Dundashill and Yoker distilleries are all names which have long disappeared from the map of Scotch whisky.

This article will look at whether factors such as price of new make spirit, ownership and production capacity are related to whether a distillery survived into the present day.

Price

The first indicator to judge whether a distillery may survive is simple; was the whisky that they were producing good, as judged by its price?

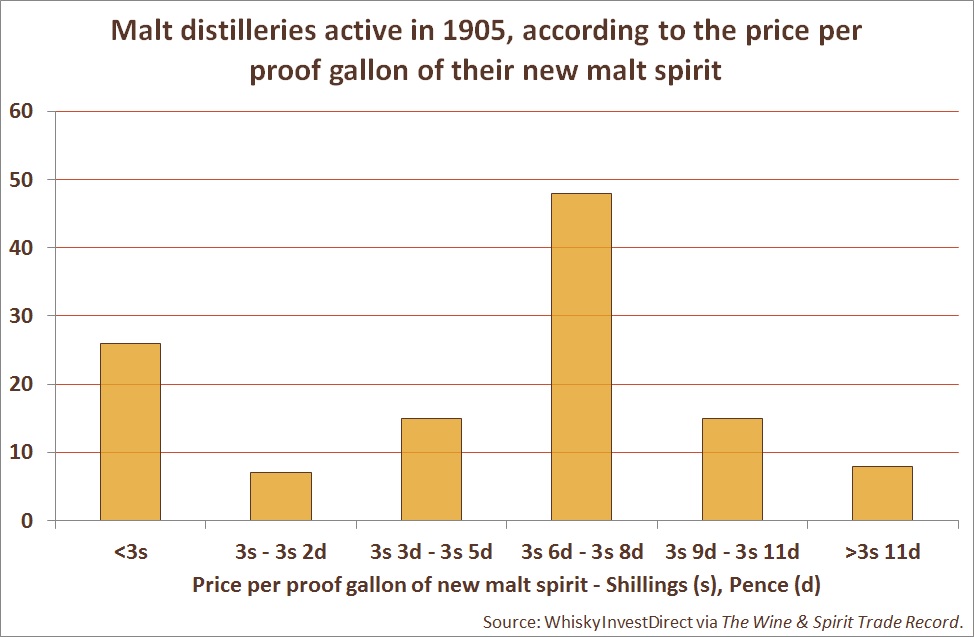

There were prices listed for new malt spirit from 123 of the 152 distilleries stated as producing malt whisky. As prices for new make spirit were identical in 1905 to those of 1899 for most distilleries, prices from the latter date have been included for Knockando and Auchentoshan. The median price per proof gallon for new fillings was 3 shillings and 6 pence, with Royal Lochnagar the most expensive at 4s 9d and Dean, at 2s 1d, the least.

As the above chart illustrates, the malt distilleries active in 1905 were compromised of a dominant middle level of distilleries sandwiched between an elite upper echelon of malt producers and a less premium lower category. Beneath this, a large sub-group of distilleries existed which produced the cheapest malt whisky.

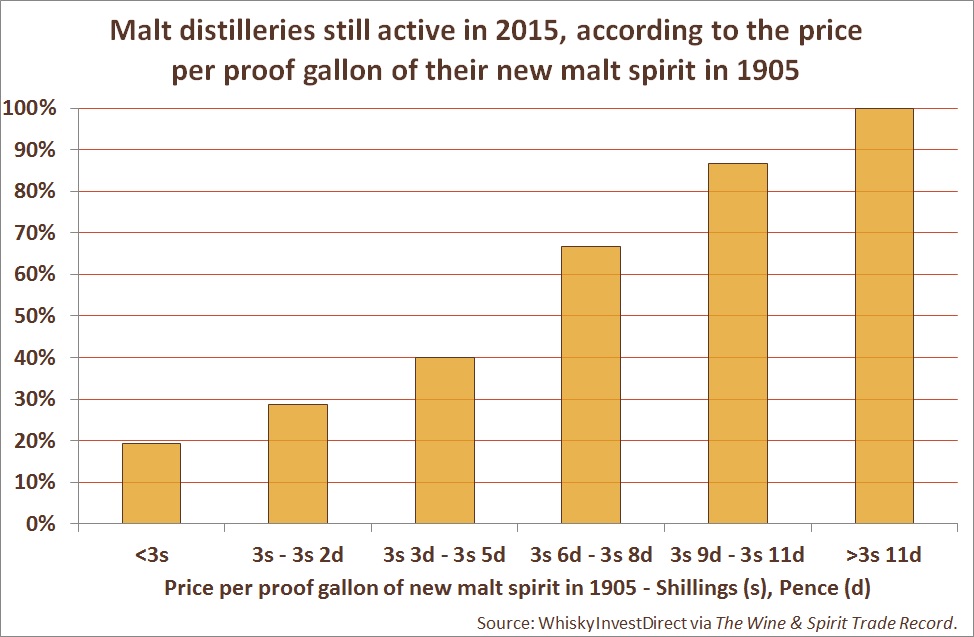

More importantly, it is clear that the distilleries which are still active today are, in general, those whose new malt spirit was more expensive in 1905. Only 22% of distilleries whose new spirit was sold in the two cheapest price categories have survived into the present day. By contrast, 91% of the malt distilleries whose new spirit was sold in the two most expensive price categories continue to make malt whisky today.

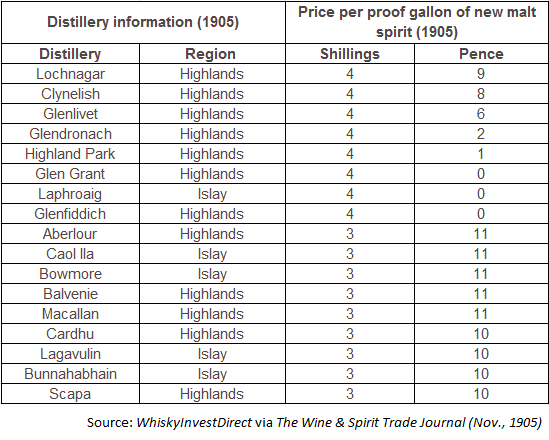

Indeed, all seventeen distilleries which charged over 3 shillings & 10 pence per proof gallon are not only still operational, but continue to be recognised as household names today:

Of course, this does not imply that all distilleries active in 1905 and 2015 have remained in production throughout the intervening period. Many have closed for short periods, while some have remained silent for over a decade at a time; Glenglassaugh, for example, was closed between 1936 and 1960 and again between 1986 and 2008. Nonetheless, it is striking that many of these distilleries were subsequently resurrected, whereas others which sold their new malt spirit for less were consigned to the footnotes of the whisky industry.

There was no relationship between the price of grain whisky and a distillery’s survival rate, owing to the small number of grain distilleries active both in 1905 and 2015. All grain whisky was priced at between 1s 5d and 1s 3d in 1905, with the median priced at 1s 4d.

Ownership

If the quality of spirit in 1905 was clearly related to a distillery’s chances for survival, did independence of ownership have a similar impact?

In the case of malt distilleries, 67% of those which formed part of a group of distilleries continue to exist in 2015, compared to 47% of those which were owned independently.

Grain distilleries were equally likely to close between 1905 and 2015, irrespective of whether they were owned independently or not. In fact, 6 of the 7 grain distilleries owned by Distiller’s Company Limited (DCL) were subsequently shut. It would appear that the underlying dynamics of the grain whisky industry have proven different to those governing malt distilleries, owing to the far greater production capacities of, and importance of technology to, the former.

Yet there are several major caveats to drawing any strong conclusions from the above. In the first place, there were 108 independently-owned malt whisky distilleries in 1905, but only 42 whose owners held more than one distillery. Clearly, many distilleries which were independently owned in 1905 were subsequently purchased by groups owning more than one distillery.

Only the recent rise of craft distilling has begun to counter this trend. Yet the difficulty of operating a distillery independently over the long-term is clear. As of 2015, only 14 of 93 distilleries founded prior to 2000 had proprietors which only owned one distillery. Indeed, the names of several ‘independent’ owners (e.g. Rémy Cointreau, Campari Group, Nikka) illustrate that the vast majority of contemporary proprietors hold a whisky distillery as part of a wider wine, beer & spirits portfolio.

Ultimately, the lifespan of a distillery depended very much on the owners themselves, regardless of how many distilleries they owned. Thus while all three malt distilleries held by W. & A. Gilbey (Glen Spey, Knockando and Strathmill) and all four distilleries held by Highland Distillery Co. (Bunnahabhain, Glenrothes, Tamdhu and Glenglassaugh) are still operational today, none of the three malt and grain distilleries owned by Jas. Calder & Co. (Bo’ness, Stronachie and Glenfoyle) lasted long into the twentieth century. Both Tamdhu and Glenglassaugh were dormant as recently as one decade ago, which further complicates any conclusions drawn from the ownership structures of 1905.

Production

After quality and ownership, a third question arises. Were the mega distilleries of 1905 or their craft cousins more likely to survive into the present day?

As production capacity was not published in the 1905 supplement, this data has been taken from Alfred Barnard’s comprehensive survey, ‘The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom’, written in 1885. The data represents the full production capacity of the distillery in proof gallons, which in 11 instances was a higher figure than the volume produced in the preceding year. Where the distillery capacity was not listed, the amount produced in the preceding year was included instead.

| Proof gallons (000s) |

Active malt distilleries (1905) |

Active malt distilleries (2015) |

Active malt distilleries, 2015 (% active in 1905) |

| > 250 |

5 |

1 |

20% |

| 200 - 249 |

7 |

4 |

57% |

| 150 - 199 |

7 |

3 |

43% |

| 100 - 149 |

17 |

3 |

18% |

| 50 - 99 |

51 |

33 |

65% |

| < 49 |

25 |

12 |

48% |

Source: WhiskyInvestDirect via Alfred Barnard, The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom (Birlinn Limited, Edinburgh: 2008).

There was little overall relationship between the production capacity given in 1885 for distilleries still active in 1905 and the subsequent longevity of the distillery, barring the disproportionate misfortune of the largest distilleries and those producing between 100,000 and 150,000 proof gallons per annum. The same is true of grain distilleries; Cameronbridge was the 4th largest grain distillery in 1885, while North British was only founded in the year of Barnard’s visit.

Again, significant caveats apply here, the most glaring of which is the gap of 20 years between the date when production capacity was measured and when the distilleries were active. The period of 1885-1905 was one of great change in the Scotch whisky landscape. From 1885 to 1899, the number of distilleries in Scotland increased by 37, before decreasing again in the wake of the Pattison scandal. As such, it should realistically be expected that significant changes in production levels occurred throughout the industry after these figures were published.

The distilleries of 1885 are completely dwarfed by the distilleries of today. Loch Katrine and Bon Accord, the largest malt distilleries of their time, had the capacity to produce approximately 779,000 LPA per annum, which would have made them the 89th largest distilleries in operation. Port Dundas, the largest grain distillery in 1885, was capable of producing 6,650,000 LPA per annum, or 6.3% of what Cameronbridge was capable of in 2015.

However, with the rise of the craft distilling movement, Scotland now possesses several malt distilleries of comparable size to the smallest operating 130 years ago. Grandtully, the smallest distillery in 1885, could produce approximately 13,000 LPA; Abhainn Dearg, founded 2008, and Strathearn, founded 2013, can produce 20,000 and 30,000 LPA respectively. There are 5 operational malt distilleries founded within the last decade which are smaller than Edradour, the second-smallest distillery in 1885, is today.

Conclusion

There are no hard and fast rules by which any business can guarantee their existence in the future. Nonetheless, the above suggests that the quality of a malt distillery’s whisky, as judged by the price of its new make spirit, has been the most important factor in deciding a malt whisky distillery’s chances for survival over the last century. By contrast, neither the size of a distillery nor the independence of its owners implies a similar level of influence.

The relationship between quality and longevity only appears to be true for malt distilleries. Grain distilleries were characterised by far higher production capacities, while their spirit was offered at virtually the same price across the board. This suggests that the fate of grain distilleries has been more technologically driven, due to the comparatively limited variation in quality between their respective whiskies. When we consider that single malt whiskies were rare in the early twentieth-century, as the vast majority of both malt and grain whiskies were used for blending, this is quite notable.

These results do not imply that whiskies from only some malt distilleries are good, or that malt alone is of high quality, since they do not factor in the aging process at all. However, there is little doubt that good whisky requires good spirit, without which time and oak can do little to improve it.

One crucial lesson which can be inferred, therefore, is that whisky is prized by consumers for its quality, and producers which recognise this are generally rewarded in the long-run.

In this light, the following advice given to exporters of Scotch whisky in 1906, written at the time when the domestic market was beginning to lose its dominance, seems prescient:

“The maintenance of quality will not only produce immediate results of a highly satisfactory kind but, by keeping up the good reputation of the trade, will strengthen its already well-laid foundations, and so help to secure its permanence.”[i]

One century on, it is the malt distilleries which heeded these words which continue to thrive.

[i] The Wine & Spirit Trade Record, ‘The Export Whisky Market in 1906’ (March., 1907), p. 131.

Leon Kuebler is Head of Research at WhiskyInvestDirect, the online platform for buying, owning and trading whisky at low cost as it matures in barrel.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.