Cask costs and overpriced oak: the economics of good barrels

In an industry built upon traditional methods and homegrown skills, casks are the only part that comes from abroad. Why do we search overseas for our oak, asks Ben Challen for WhiskyInvestDirect...

As ANY ADVOCATE of Scotch whisky will tell you, the cask it’s aged in is of vital importance, imparting the flavour and maturity that makes Scotch a global powerhouse in the spirits industry.

Sourcing the best wood is a large part of making the best whisky, and new figures from the Scotch Whisky Industry Review predict that over the next 4 years the volume of Scotch whisky stored in cask will rise by 12%.

So what happens when demand for new casks stretches supply?

Since coopers’ unions in America lobbied to include the word ‘new’ in legislation defining bourbon whiskey back in 1935, all bourbon has been made in brand new American oak casks made specifically for the purpose.

The subtext to that, of course, is that after being used once, they need to find a new loving owner, and the Scotch industry (which has no such qualms about reusing casks) is comfortably their biggest buyer. For the last 80 years, they have shipped casks across the Atlantic as disassembled staves and rebuilt them either into their original barrel shape, or into the slightly taller hogshead size by adding new ends.

This special relationship has long been far more harmonious than any in the political spectrum, and prices of ex-bourbon casks used by the Scotch industry tend to be influenced by factors at the source, i.e. the health of the American whiskey industry and, one step further back, the health of the American lumber industry.

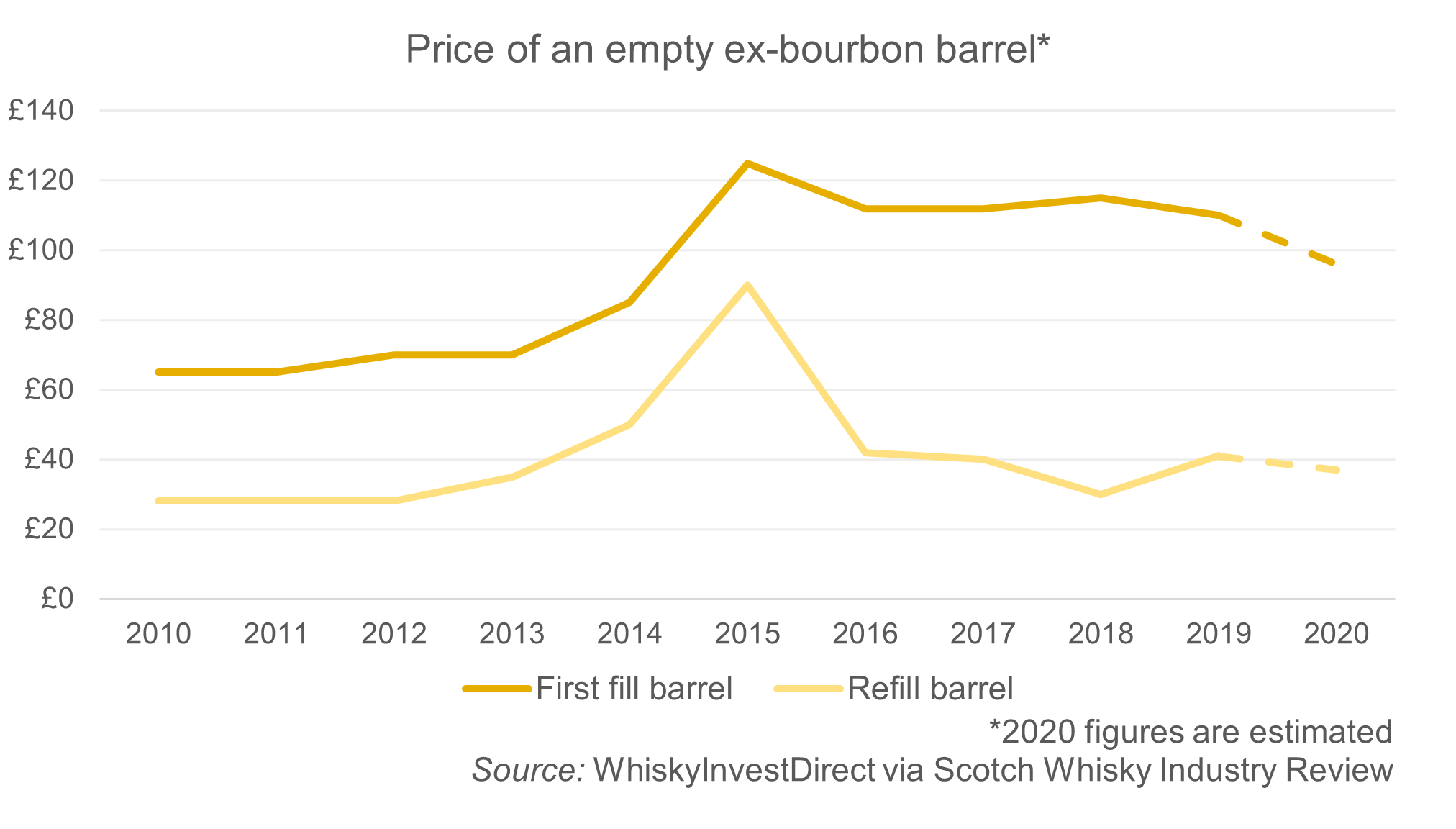

Since around 2010, the whiskey industry has shown strong growth, led by the “bourbon boom”, but this only served to put more demand on a lumber industry that was reeling from the housing crash in 2007. The result was a spike in cask prices both in the US and in Scotland, which peaked in 2015.

The onset and aftermath of that spike is an interesting study in market dynamics. Although refill casks do not have as direct a link to these factors at the source, since they already exist within the Scotch industry, they nonetheless saw the same spike in cost. Distilleries who would age their whisky in first fill bourbon casks and then sell them on as refill casks needed to offset the increased costs they were seeing in getting hold of new first fill. However, once the market was satisfied that costs were stabilising, the greater number of refill casks in the market bore down prices very rapidly, and by 2016 normality had returned.

However, while a refill cask can stay in the market for 50 years or more and be reused multiple times, distilleries in search of first fill ex-bourbon casks had only one place to turn – back across the Atlantic.

While the price of making bourbon barrels was also starting to stabilise, the bourbon boom was keeping the supply/demand curve stretched taut, and once again bourbon producers were recouping the costs by increasing the price at which they sold to the Scotch industry. The result was a much slower drop-off in price – only in 2020 does it really look like barrel prices might be dropping back to pre-2015 levels.

This means that for a few years from 2016-2019, first fill casks were relatively harder to find than refill casks – while the difference in cost between a first fill barrel and a refill barrel had hovered around £35-40 in previous years, in those 4 years it averaged over £70.

But is there anything to be read into this? Many distilleries in Scotland have good working relationships with distilleries in America – for instance, Diageo own enough bourbon distilleries to ensure that their distilleries in Scotland get a steady supply of the right casks, and Laphroaig get the vast majority of their ex-bourbon casks from Maker’s Mark. These distilleries will have ensured that they kept their cask profiles at the usual levels, even if the costs went up briefly.

However, distilleries with less solid supply chains, and those primarily making whisky for the purpose of blending, may have been tempted to cut costs by aging more of their whisky in more affordable refill casks. Only in the last year or so will they have been able to return to normality.

Of course, while ex-bourbon casks are the most common type used for aging Scotch whisky, they are far from the only type. Watch this space for a look into the factors behind the cost of a sherry cask.

Commercial Director at WhiskyInvestDirect, Ben Challen is at his happiest when surrounded by whisky and statistics, sifting through the data to find out what makes his favourite industry tick.