Blends vs. Malts: Whisky's misplaced divide

It's time to rethink the relationship between Scotland's major whiskies...

“TOM, you know about wine,” friends would say. “Chardonnay’s a bit naff … isn’t it?” Well, not if you include most Champagne, every bottle of white Burgundy and countless others too, writes Tom Bruce-Gardyne for WhiskyInvestDirect.

But of course, that’s not the response required. This little nugget of misinformation demands a simple nod of the head, even though it’s an out-dated view inspired by the blowsy, over-oaked Chardonnays that Australia stopped producing decades ago.

By the same token: Single malts are better than blends … aren’t they? Well no they’re not, and nor can you really compare them. By carefully choosing an array of malt whiskies and binding them together with grain whisky you can be far more creative with blends than single malts which contain the same liquid every year.

Single malts and blended whiskies are created by a master blender who will be vatting up casks of Talisker or Macallan one day, and blending Johnnie Walker or Cutty Sark the next. Whether you call it ‘vatting’ or ‘blending’, it’s the same job involving the same skill and care.

Grain whisky may not have the romance of pot still malt whisky, but it is matured in the same way and can be sublime with a bit of age. Try the aptly-named Hedonism, a blended grain from Compass Box, and you will be seduced.

As for the blenders themselves? They would never dream of saying malts are inherently superior to blends.

So who is to blame for propagating this urban myth? Well, first in the firing line would be whisky writers [myself included] and the flood of whisky books that has followed the boom in single malts.

While bottles of malt had always been around, they had never been pushed on a commercial scale until 1963 when William Grant’s launched Glenfiddich Straight Malt, which eventually became a 12 year-old single malt.

These age statements matter because originally malts competed head to head with ‘deluxe blends’ like Chivas Regal and Johnnie Walker Black Label which have always been 12 year-olds. The age stuck, ensuring a significantly higher price for malts above the sea of standard blends, and that in turn reinforced the idea they were somehow ‘better’.

Back to books, and a formula soon emerged: cover the process focussing on pot stills, explore the malt whisky regions with distillery profiles and atmospheric pics, and then, if space allows, mention something about blending. From reading them you would never guess that single malts account for just 10% of all Scotch whisky sold. Yet in defence of whisky writers, an essay on the art of producing a consistent blend will never be as sexy as a storm-tossed distillery on Islay, and nothing like as photogenic.

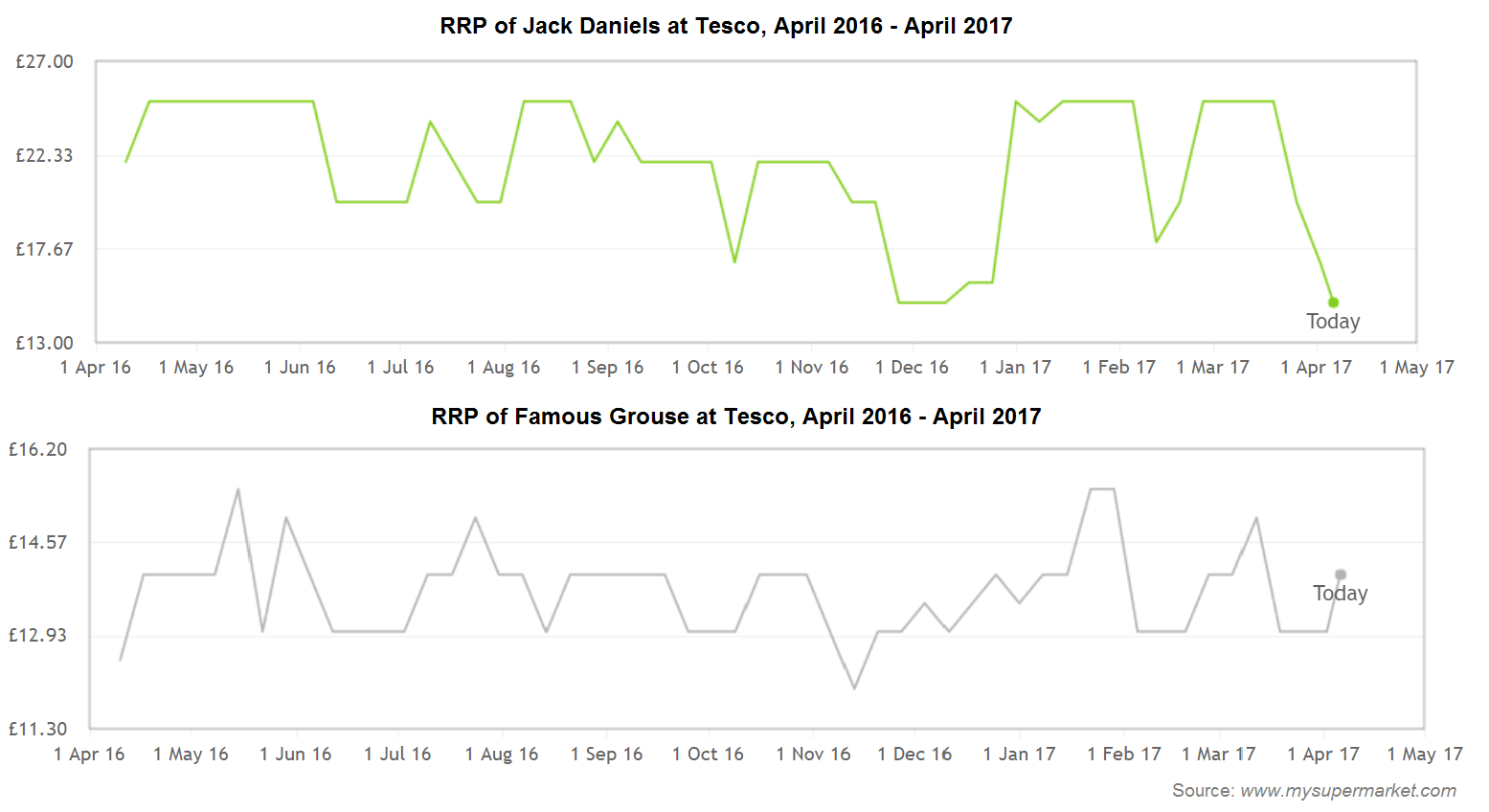

Demand for blended Scotch remains strong in much of the world, in countries as diverse as Poland, India and Mexico - now the third biggest importer of bottled blends thanks to brands like Buchanan’s and Black & White. Yet the industry has been complicit in allowing standard blends to stagnate in mature markets where the big brands are caught in a spiral of deep discounting in their fight for market share. If Famous Grouse is still ahead of its arch rival Jack Daniel’s in Britain, it may be down to its perpetual price promotion [see below]. Their production costs can’t be that different, but the American has a more premium image because consumers naturally equate price with quality.

Single malts have risen in price and prestige, allowing the brands to reinvest in fancy packaging and endless new expressions, while a standard blend at £13 leaves just £2.35 after tax for the distiller and retailer to squabble over. Beyond the mature markets however, there is genuine respect for blended Scotch so one shouldn’t generalise, and there is a real self-confidence in blends like Ballantine’s, Buchanan’s and Johnnie Walker.

More to the point if you just stick to drinking single malts you would be missing out on some beautifully subtle, complex whiskies like the Compass Box blends, Johnnie Walker Black Label and indeed the new James Eadie Trade Mark X blend.

Like Chardonnay, the real issue for blended Scotch is one of image. We should be wary of sweeping statements and remember that old adage: a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

Award-winning drinks columnist and author Tom Bruce-Gardyne began his career in the wine trade, managing exports for a major Sicilian producer. Now freelance for 20 years, Tom has been a weekly columnist for The Herald and his books include The Scotch Whisky Book and most recently Scotch Whisky Treasures.

You can read more comment and analysis on the Scotch whisky industry by clicking on Whisky News.