Difference in price between Scotch whisky producing regions

One question which we sometimes receive is: 'Does the region in which a whisky is produced have an impact on its price?'

There are two types of Scotch whisky: malt whisky and grain whisky.

Malt whisky is defined by the geographic region in which it has been produced: Speyside, Highland, Islay, Lowland and Campbeltown. Grain whisky is not defined by region.

There is no information currently available in the public domain to indicate whether malt whisky produced in one region is generally more or less expensive than another.

The Scotch Whisky Industry Review publishes broking prices for Scotch whisky every year, dating back to 1972. These prices are divided according to two factors: type (malt or grain) and age of the whisky concerned. They do not differentiate between distilleries or regions.

Until 1970, however, the new filling prices of individual whisky distilleries were listed in another publication, The Wine and Spirit Trade Record. The region which each distillery belonged to was also noted, although all Speyside distilleries were listed as 'Highland', as the Speyside region was not yet formally established. We have included all distilleries located in what is now known as the Speyside region as a separate category for indicative purposes.

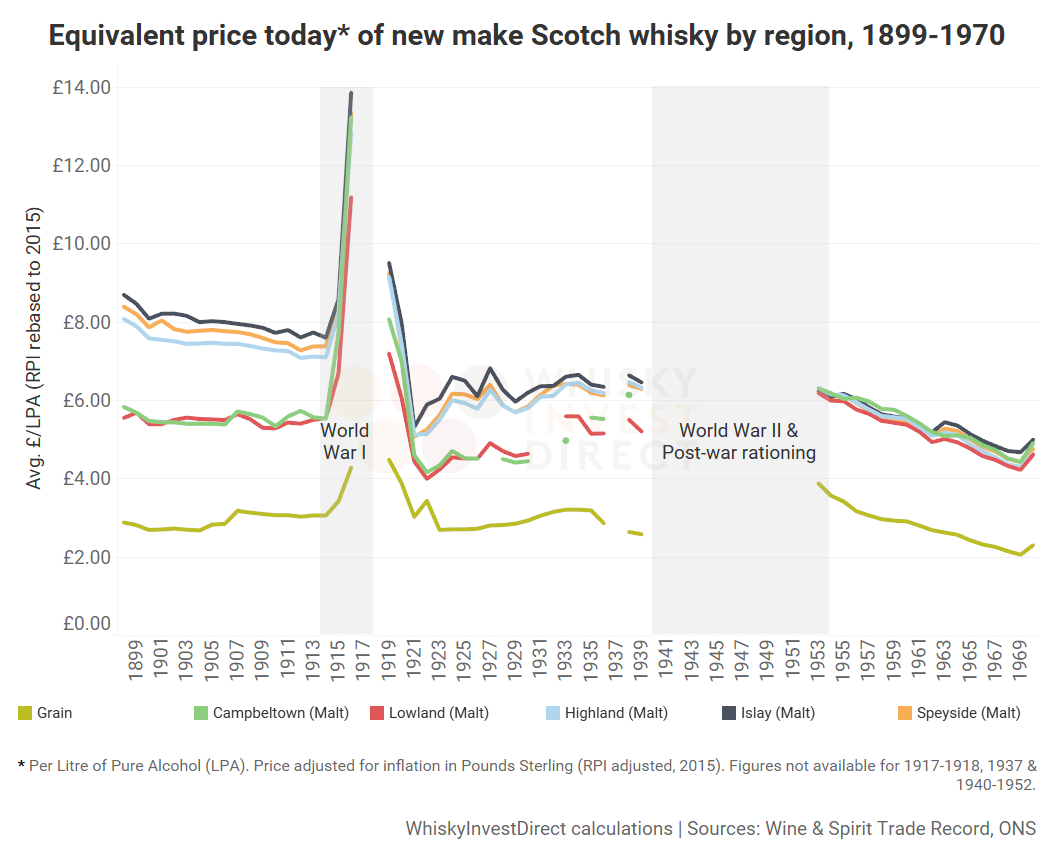

Figures were given for most active distilleries in every year, with three notable exceptions: 1917-1918, when there was a total wartime prohibition on distillation; 1940-1944, when a near-total wartime ban on distilling was again enacted; and 1945-1952, when post-war restrictions on distilling and grain rationing were still in place.

Data was only given for newly-made whisky. Prices for mature whisky were not given.

The chart above shows the average price of a Litre of Pure Alcohol (LPA) of new whisky from each region in today's money (i.e. after inflation).

Before the Second World War, newly-made malt whisky distilled in the Highland, Speyside and Islay regions cost significantly more to buy than that made in either the Campbeltown or Lowland regions. In 1899, new Lowland malt cost, on average, two-thirds of the price of new Islay malt. By 1939, the gap had narrowed, but new Lowland malt was still roughly 20% cheaper than malt produced on Islay.

After restrictions on distilling were completely lifted in the early 1950s, however, there was very little difference between the average new fillings prices of different regions. In 1953, there was only a 2% difference in price between new malt whisky made in the cheapest region (Lowlands) and the most expensive (Highlands). By 1970, the gap between lowest (Lowlands) and highest (Islay) had grown to 8%, but was still very small compared to pre-war levels.

What caused this change? There are three factors that likely made region less influential on the price of new malt whisky.

Firstly, many distilleries closed in the early twentieth century, due to the economic turmoil caused by the 1899 Pattison scandal, the First World War and the interwar depressions. The majority of distilleries which ceased production were those making cheap malt whisky; by contrast, those distilleries which could charge more for their new-make spirit were far more likely to survive to the present day. Since cheaper malt whisky should be more attractive to blenders, as it reduces their cost of production, this suggests that the distilleries which closed were producing spirit which blenders did not want for their products – either due to concerns over style or quality. Many of these closed distilleries were located in the Lowlands and Campbeltown. Those that survived in these regions were, presumably, producing better-quality whisky which they could charge a higher price for. This narrowed the price gap between them and other regions.

Secondly, a small number of large companies came to dominate the whisky industry over the interwar period. These corporations often held malt distilleries in multiple regions, and they appear to have charged the same prices for new malt spirit. In 1957, for example, all 38 malt distilleries owned by Scottish Malt Distillers, Ltd. were offering their new fillings at the same price, irrespective of the region which they were located in. By 1970, Scottish Malt Distillers was again charging different amounts for new malt whiskies, but region was largely unimportant to price: three of their six most-expensive malts were made in the Highlands; but so were three of their six least-expensive.

Thirdly, the cost of distilling in more remote locations (such as Islay and other islands) was far higher at the beginning of the century. This was primarily due to the cost of local raw materials and transportation. Over time, the introduction of economies of scale and more efficient production methods has generally caused the cost of new make spirit (both malt and grain) to decline in real terms. This trend has continued to the present day.

In short, the region which a whisky was distilled in became less influential on the price of new make spirit over the first seven decades of the twentieth century.

Of course, given that the most recent data given here is 47 years old, it may not reflect the current state of the whisky market. Nevertheless, the long-term trend suggests region became less significant to price as quality of distillate, economies of scale and production methods became more uniform across the industry.